Westerns: The Rural Video Store

by Milo Muise

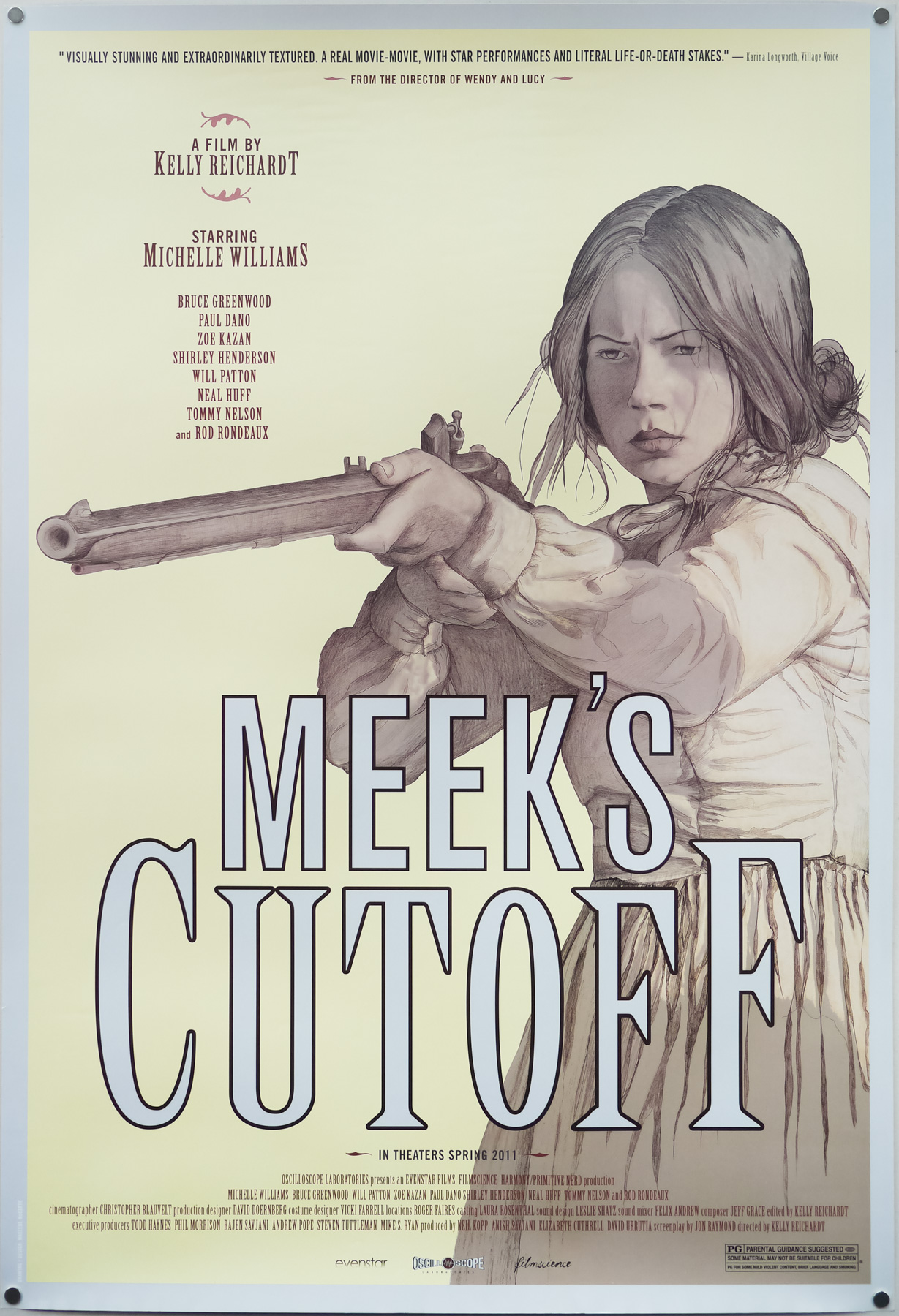

Meek’s Cutoff (2010): Accessibility

In the ultimate depressing cult children’s movie (how’s that for a genre you won’t find on Netflix), Babe: Pig in the City (1998), George Miller—Yes, the George Miller of Mad Max fame—tells the story of a pig who must leave for the city, hoping to make enough money to save the farm he calls home.

It’s a familiar tale that sets up a common dichotomy between the country and the city: the former is a charming idyll, while the latter is a cultural hotspot. With places like Howard Hughes Video Store and the Kenworthy Performing Arts Center, Moscow, Idaho tested the truth of these (dubious) claims, offering its residents an access to art and entertainment that would be notable no matter the population size.

Howard Hughes Video Store didn’t just give Moscow access to movies; it gave Moscow access to the world beyond the town’s isolated borders. Before going to Howard Hughes, Melinda Schab had never seen a foreign film . Martin McGreevy would spend time in the European section , where he discovered Lynne Ramsay’s Ratcatcher (1999) and German arthouse films.

Mitchell Lopez likens the video store to his family running the Mexican restaurant La Casa Lopez: not everyone can afford to travel to Mexico, but they can get a taste of it at the restaurant. Using employee recommendations and an eclectic list from his dad, Mitchell began to “understand what our world was made of.”

Movies also opened up a sense of possibility, especially in younger viewers. They might discover their future career depicted on screen, find their songwriting influenced by film scores and soundtracks , or seek out an engineering career after being inspired by the technical aspects of sci-fi movies.

Some endeavored to go into the film industry itself. Luke Gresback is now a filmmaker in Los Angeles (“kind of an annoying sentence to say,” he apologizes ) who credits his artistic sensibilities in part with the movies he rented from Howard Hughes.

After renting Pi (1998) as a teen, Martin McGreevy moved to New York City and ended up

working with director Darren Aronofsky on some of his later projects, including Black Swan (2010).

Black Swan (2010)

Russell Meeuf, who now teaches film and media studies at the University of Idaho, first got into the habit of studying movies thanks to his childhood video store rentals.

Howard Hughes also gave residents a reliable way to watch movies even as the internet became more robust. Into the late 2000s, internet service in rural areas was still limited. Video files were especially large, and your viewing experience would be plagued by lags and buffering if your connection wasn’t up to the task. As a result, many stuck with VHS and DVDs.

We were out in the country and had a horrible connection to like any network, so we would just always rent movies.

Howard Hughes was a store that knew and loved its clientele, even slowing its transition from VHS to DVD to maintain access for those who were reluctant to adjust to new technology. As movie theater prices skyrocketed, the video store was an affordable place to stay current on new releases (if you were willing to wait).

In his interview with Bekah Miller MacPhee, Beau Newsome reflects on how “cool and rare” it was to have Howard Hughes as a resource in Moscow:

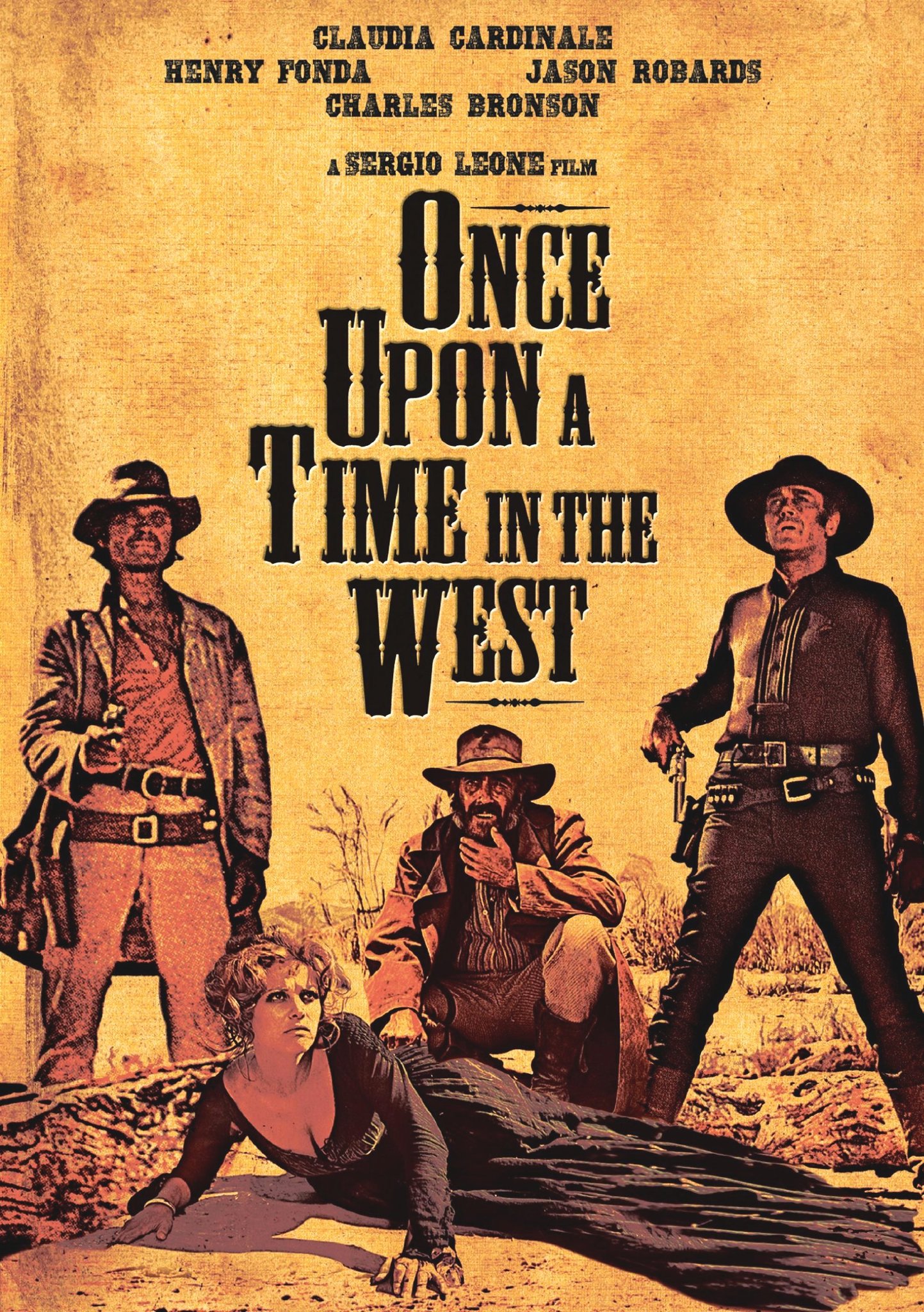

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968): Customer Recollections

When you ask the customers of Howard Hughes Video Store what they loved about the store, their answers are as vast as the store’s movie collection but united by a common reverence. Multiple interviewees referred to it as a sanctuary, whether for film fans or from the perils of high school .

It was a place that fostered connection amongst families, friends, and the greater Moscow community, but just as importantly, it was a fun place to be. Unlike the more clinical stylings of Howard Hughes’ chain competitors, “I liked the feeling of walking into Howard Hughes. It felt like a friend’s house .

If the store was a friend’s house, the staff were your friends, always ready to dispel some cinematic wisdom or introduce you to a new favorite movie. If you weren’t too intimidated to ask,you might learn about the 20-minute dance/fight scene at the end of The Boxer (1997), or why Tarantino makes up fake restaurant names for his movies, or the punk filmmaking of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974).

Point Break (1991)You could also test your own knowledge by answering the store’s trivia question and enter to win a free rental. For a taste, try Beau’s favorite question: “In Point Break (1991), which presidential mask did Keanu Reeves wear?”

Click here for the answer .

While checking out, your selection might be validated with a “Wait until you get to this part,” or, “Oh, you’re going to like this.” Netflix doesn’t have that personal contact , says Janice Willard.

You could also look to other customers for suggestions. Kenton Bird describes the pleasure of being in the store’s aisles with other browsers:

In the video store, the great question of our era played out in real time: what are we going to watch? Is this worth a full-priced rental, or should it be saved for 99 cent night ?

Elijah Ting remembers crowding in the store with his family , looking around and debating their options.

It was like a really magical time to contemplate going to the store and getting to watch a film, and then we would watch it as a family and like make popcorn and everything.

The bulk rental deals were especially helpful in allowing everyone to find something they wanted (and preventing too many in-store meltdowns).

The selection was just the beginning of the renting ritual. Many families described watching the films together and discussing them afterward. Howard Hughes supplied Lauretta Campbell with the movies she needed for everything from sleepovers with her sisters to her family’s (incredible!) tradition of watching bad James Bond movies on Christmas morning.

“For my family, at least, the video store, it just offered a family connection for us .”

Movies were also a way of connecting across generations. Watching the 1985 series MacGyver gave Eric Nilsson and Janice Willard’s kids insight into their parents’ generation and cultural touchstones. Professor Ben Beard required his classes to watch The Princess Bride (1987) so that they would understand his jokes .

Film connects people across time: whenever you watch a film, you become a part of every audience that has ever seen it. Here, Monique Lillard recounts her family’s experience watching the 1932 Laurel and Hardy movie The Music Box:

Even after the movie was over and returned (hopefully without a late fee), the experience remained. Movies gave families and friends a shared language, a form of communication that lives on far beyond the scroll of the credits or the closure of a video store.

Stagecoach (1939): The Moscow Community

Blockbuster Video StoreBack in the heyday of video stores, they were everywhere. Chains like Blockbuster and Hollywood Video popped up across the country, and many now-nostalgic childhood memories were made amongst their shelves. Howard Hughes Video Store stood apart as a small independent business—a store that was by the community, for the community.

Before there was Howard Hughes Video Store, there was Howard Hughes Appliance. Open since 1960 and still operational today, they started their movie collection to encourage VCR sales. Customers would get 25 free rentals with the purchase of a VCR , a promotion that set Howard Hughes apart from its non-renting competitors like Sears and Duranleau’s.

The plan worked, and Howard Hughes began acquiring more tapes, eventually growing from a corner in the appliance store to its own brick and mortar location. Even after the appliance store stopped being financially tied to the video store, Howard Hughes would sometimes offer free rentals to make an appliance sale happen .

Whenever the store faced an uncertain future, the community stepped up. In 2007, four local business owners banded together to buy the store, ensuring it stayed open–despite the fact that none of the new owners were particularly passionate about movies. Gary Myers, Kelly Moore, Pat Engle, and Deb Reynolds were essential to the store’s longevity.

The video store became one of the gems of downtown Moscow. Its central location made it a meeting place for the community: “ You’d see everybody , everybody who’s anybody at the video store, and you’d stop and have conversations in that very Moscow way that we do.”

Residents would stop in after grabbing coffee at One World, or lunch at Mikey’s, or seeing a movie at the Kenworthy and get their video fix before heading home.

The Kenworthy had an especially close relationship with Howard Hughes. If the Kenworthy’s projector ever stopped working, or an issue arose with their planned screening,

We just ran down the street and said, ‘What can we show for free this weekend?’ and we were always able to find something.

The video store would trade the Kenworthy free rentals for their Saturday morning cartoon series in exchange for cast-off movie posters .

Eventually, the Kenworthy was the recipient of the video store’s enormous collection (more on that in the Horror section), a process that helped keep the Kenworthy staff employed during the early days of COVID-19.

When the then-current owners were looking to step away from the business, the community came together once again to save the video store, this time deciding to switch from a private to cooperative business model. Those at the helm believed this would be an advantageous way to keep the institution alive while distributing the work involved to keep it running amongst a larger group.

As the Main Street Video Co-op, customers could pay a $200 fee (which could be paid in installments) to become an owner, affording them special deals and discounts as well as a stake in the business. The Moscow Food Co-op, heeding the principle “Cooperative cooperation among cooperatives,” was a tremendous support to the fledgling video co-op, educating their board, offering graphic design support, and donating equipment .

In the face of the video store’s shuttering, Cody Moore offers a passionate plea to frequent the stores that remain and reminds us what is lost when a part of the community folds:

You can still see remnants of the store around town: the shelves that used to hold videos were donated to the food pantry at Inland Oasis. Sandra Kelly says that it gives her joy whenever she sees them knowing they traveled from nonprofit to nonprofit.

Even the creation of this oral history project is a testament to the Moscow community’s commitment to and love of Howard Hughes.

Click a spine below to explore other sections of this essay:

![University of Idaho Library [logo]](https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/media/digital/liblogo_transparent.png)