Horror: The Nail in the Video Store’s Coffin

(…or is it?)

by Milo Muise

It Follows (2014): Main Street Video’s Final Days

Moscow Street Video Co-op closed permanently as of March 2020, due to a perfect storm of factors. Despite the efforts of dedicated customers like Bekah Miller MacPhee who would call the store to see if they had a movie before streaming it, the store’s recent years saw a marked decrease in renting and foot traffic.

Netflix began renting out DVDs by mail in 1998, a service that grew increasingly popular in the 2000s with people swapping their trips to the video store for a trip to the mailbox. (There’s a rumor that Netflix’s founding was inspired by a particularly egregious Blockbuster late fee , though this might just be a “convenient fiction”.) Then came streaming, which didn’t even require you to leave your couch.

Cody Moore comments, “You really have to kind of convince people that [renting] is a better way to consume movies than just clicking a button or on your phone or the TV.”

Benjamin Hardcastle thinks RedBox might have had an even bigger negative impact , given that they made it easy to rent new releases and were placed at convenient locations like grocery stores. In addition, parking was notoriously difficult on Main Street, and the co-op didn’t have a parking lot.

The store also didn’t have a strong online presence. While many think offering online ordering would have helped, it simply wasn’t feasible given the store’s limited resources. As Lauretta Campbell explains:

For a sense of what that process might have entailed, Scarecrow Video in Seattle recently fundraised $200,000 to update their website and store infrastructure, allowing for more robust searchability of their collection, recommendations, and real-time inventory updates. Kate Barr says, “If we’re going to be serious about continuing to exist into the 21st century, then we need to be able to interact in a 21st century kind of way .

The switch to a cooperative structure introduced some new challenges as well. The board, while incredibly dedicated and hardworking, were also all volunteers, and many were having to run their own businesses on top of their co-op duties. A large portion of the customer-owners who pledged to pay their ownership fee in installments stopped paying before they met the necessary $200, meaning that the store didn’t have the funds they had anticipated .

The membership fee might have given some sticker shock , especially when streaming services take the opposite approach, asking for small monthly payments rather than a large upfront sum. (Though those small fees add up as one’s number of subscriptions grows.)

Then, COVID-19 arrived in the winter of 2020. Suddenly, many were stuck at home, tired of their streaming options , seeking the kind of curated variety the co-op had in spades. The living room was the only open theater in town, and many were wanting to stock up on videos to watch at home . The social distancing requirements could have provided opportunity for contactless rentals or a delivery service.

However, by that point the store was struggling so severely that implementing these kinds of projects was impossible.

Not long after the co-op announced its closing, the Kenworthy reported that it would sell the co-op’s 30,000-movie collection. Melinda Schab was devastated at the news. She had hoped that there was a chance that the store might be resurrected if the collection had been preserved .

The speed of these decisions along with limited communication and the emotional fallout of losing this collection resulted in a host of rumors about how and why this deal took place. So, let’s set the record straight:

-

The collection was not sold to the Kenworthy; it was transferred there as a debt settlement , resolving a balance the co-op owned to the store’s previous owners.

-

While the Kenworthy tried to find a library or organization willing to take the collection intact, there wasn’t enough interest. The collection takes up such a substantial amount of space— roughly 1400 square feet —that even finding a place to store it would be difficult.

-

The Kenworthy did not sell the entire collection. They retained over 2000 items including important pieces of cinematic history, the Criterion Collection,

PFFF flier from 2016 French films (for the annual Palouse French Film Festival), and the entirety of Mystery Science Theater 3000. While they don’t foresee renting these to the public, you can rent out the Kenworthy to watch what they kept. -

The sale items were largely dispersed locally. Pieces of the collection can now be found in the homes of Moscow residents. The Palouse Cult Film Revival, a nonprofit bringing cult film awareness to the community, received roughly a quarter of the cult section. The University of Idaho library took in everything that didn’t sell to the general public and is currently working on how to make this collection available to the community .

For Monique Lillard, “These interviews have brought back for me how much I loved the store, and how much I really mind that it closed .

Lauretta Campbell finds it bittersweet but comforting to know that the movies at the Kenworthy and all the work they represent will still go on to benefit the community somehow, just not in the form of a video store .

But like every movie, the credits have to roll at some point. Lauretta admits, “The video store was very much loved, and it was a huge benefit to have, but I think everyone kind of knew that it wasn’t going to be here forever .”

Don’t Look Now (1973): What’s Been Lost

When looking at the history of cinema, one adage proves true: the only constant is change. Moviemaking is a unique marriage of art and technology, so with advances in technology come innovations in films and their distribution. Often, these developments are met with resistance.

In the late 1920s, the silent film era was ending, with “talkies” synchronizing sound and image for the first time. Silent film stars were not pleased, and there was a general sense of nostalgia for silent films, not unlike the nostalgia many of us feel for 35mm film and other technologies rapidly becoming a thing of the past.

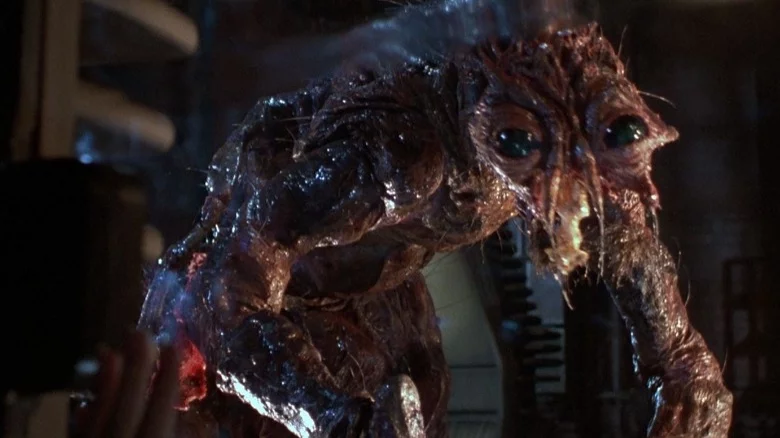

Practical effects in The Fly (1986) That’s not to say that all progress is good progress or that we should automatically welcome the rise of CGI with open arms. (I personally remain an ardent lover of practical effects.)

Rather, it’s to point out that when we are nostalgic for VHS or the video store, we are joining a long lineage of nostalgic film fans. Nostalgia might define cinematic history more than any other affect.

So, let’s take stock. What’s the difference between renting and streaming? What do we miss when we miss the video store? How do our watching habits signal shifts in our cultural priorities and values?

Undeniably, streaming is more convenient than having to take a trip down to the video store (and then another trip back to return your movies). With streaming, you have immediate access to a large amount of content with the click of a button. You no longer need to schedule your life around when your favorite TV show happened to be airing . There’s no worrying about a scratched disc or late fees .

Dan Orozco admits, “I just got lazy… The new technology is really kind of insidious .

Streaming can give you the sense that you have access to an unlimited amount of media, but that promise is more illusory than people think. Kate Barr from Scarecrow Video explains, “The thing that Netflix has done the best is sell the idea that everything is available online, because in reality it’s just not even close…If you take Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu’s collections and you put them all together it’s about 36,000 titles, and we have over 140,000.”

Streaming services also rotate their selection depending on factors like a title’s popularity or licensing agreements, and you can’t make requests the way you could at the video store. (I suppose you could tweet at Netflix, but the likelihood they would actually respond to your ask is slim.)

Immediate, unlimited access might even be detrimental to audience engagement. Bekah Miller MacPhee describes feeling more immersed in the experience of watching a movie back in her renting years. Going to the video store fostered more of a relationship with a movie:

Having too many options can result in a paralysis of choice, and Howard Hughes’ curation circumvented the “doom scrolling” that often accompanies finding something to watch on a streaming platform. The “event” of picking up a movie and popping it into your DVD or VHS player made for a more of a captive audience.

“I was more likely to watch a whole movie from Howard Hughes because of the extra effort,” says Martin McGreevy.

In the West, we’ve been following a trend away from the communal and toward the individual for a while now, whether it be swapping public transit for cars, payphones for cell phones, or movie theaters for home theaters. The video store was an interesting liminal space : a social meeting ground supporting a solitary (or intimate, at least) venture—watching a movie in the privacy of your home.

While many valued the sociability of going out and having somebody to engage with about movies , there’s always those who would rather skip the human interaction.

After all, existing in society comes with its drawbacks, as anyone who’s had a movie theater experience ruined by someone’s loud talking can tell you. For Monique Lillard, though, the tradeoff is worth it: “Moments when the whole audience gasps or laughs enhances the experience, too .

While we’re right to pay attention to the changes that come with streaming, we can be careful not to fall into a trap of romanticization. Russell Meeuf explains,

Martin McGreevy sums up the hope of many in the Moscow film community:

I just hope that film as a medium continues and we're not all the more sequestered in the virtual reality headset… I think I always hope for you know the experience where we all sit in front of the modern cave painting and watch a film.

Frankenstein (1931): How to Reanimate the Video Store in the 21st Century

If there’s one thing a good horror movie knows, it’s that the dead are never really dead. While Main Street Video Co-op is closed, that doesn’t mean we can’t recapture some of what we loved about it. Here are some suggestions to get you started:

Do you miss the curation?

-

Kanopy is “the closest thing to a virtual video store” according to Benjamin Hardcastle. This streaming service partners with public libraries and universities, offering free access to a wide variety of both classic and contemporary cinema.

-

The Criterion Channel provides you with a rotating selection of their catalog, including curated spotlights on directors, genres, and themes.

-

Mubi is a streaming service that boasts hand-picked film curation. They offer a limited, rotating selection of films, much like your favorite “employee picks” shelf.

Do you miss getting to talk to people about movies?

-

Get into podcasts! You just might feel like you’re back in the video store overhearing conversations between customers and staff.

-

Join the Letterboxd community to log and rate movies and converse with fellow film lovers.

-

Go to the Kenworthy or your local movie theater. If you’re in Moscow, you can rent the Kenworthy and screen whatever you want with whoever you want!

-

Get involved with a local film group, like the Palouse Cult Film Revival, or start one of your own.

-

If documentaries are your thing, Influence Film Club helps you set up your own film club and offers discussion guides, director interviews, and more to “support real people having real interactions more often.”

Do you miss tangible media?

-

Use Scarecrow Video’s rent-by-mail service! Scarecrow Video will mail you your rental along with a return mailer, and you can enjoy their incredible collection from home.

-

Movie Madness in Portland, OR If you’re wanting an in-person experience, head to Seattle to visit Scarecrow Video or Portland to check out Movie Madness. In addition to its 80,000-title collection, the latter features a museum with movie memorabilia, including pieces from The Godfather: Part II, Psycho, Fight Club, and Pulp Fiction. (As a lover of Movie Madness, I’ll also plug that they have have an incredible horror section delightfully organized by the films’ horrific element, including “perverted science” and “killer kids.”) -

Fuel your nostalgia and watch some 35 mm film trailers.

Do you miss browsing?

- Go to your local library! There, you can walk the shelves and wander through not just their DVD collection, but also books and periodicals. Some libraries (like the University of Idaho’s) also have game libraries and other surprising collections.

Do you miss bonus features?

-

Youtube hosts a wide variety of filmmakers and film enthusiasts sharing their craft.

-

Criterion’s Current is full of insightful film criticism that will give you a deepened understanding of important films.

-

Listen to these audio film commentaries, now available online.

Do you have an inordinate amount of time and/or money?

- Build your own video store in your basement, like this guy did.

There’s no replacing Moscow’s premiere indie video store, but its legacy lives on in the community members who supported and staffed this downtown gem. Thanks for 30 movie-filled years!

Click a spine below to explore other sections of this essay:

![University of Idaho Library [logo]](https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/media/digital/liblogo_transparent.png)