Victoria A. Sierra Item Info

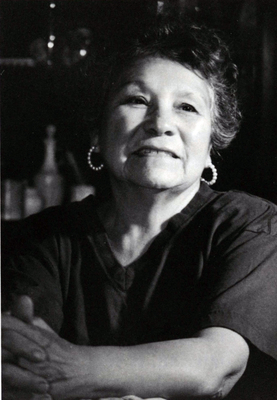

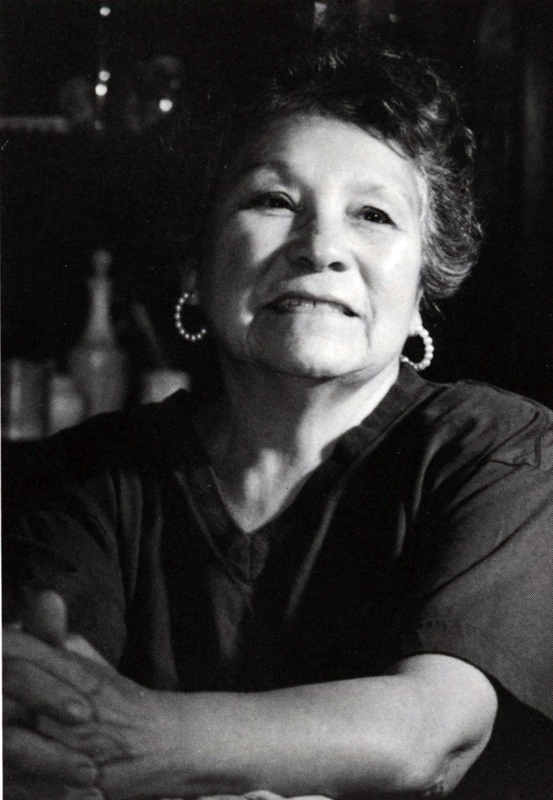

00:03 This is an interview with Victoria our two letter Sierra by Angela lucky for the oral history project of the Idaho commission on Hispanic affairs. The interview took place on January 10 1991, in Mrs. Sierra’s home 317, South Third, Pocatello, Idaho. Mrs. Sarah talks about her family and their experiences as they begin living in Idaho.

00:51 Do you know when your family came to this country?

00:54 Will my family already lived here in the States My father was born in a little town called Chowpatty doe in the state of New Mexico. And my mother was born in a little town named Higbee. In the state of Colorado. And as far as I know, they’re people were born in the in the States. I don’t really know anything more about about where they came from, to here except they were already there. In New Mexico and Colorado.

01:33 Do you know about your grandparents?

01:36 No, they I think that my great great grandmother on my mother’s side was Indian, American Indian. But I don’t really know what tribe or I don’t know anything about her. My mother’s mother died when she was six years old when my mother was six years old. And then so they lost track of everything they never, she had to go live in a cattle ranch with her dad. So they they lost track of everything nobody had ever explained anything to them. And my dad will. His parents died when he was six years old also. So he never had any family history of any kind. Except that they were all born in New Mexico.

02:35 So how did your family then come to Idaho?

02:40 Well, my dad traveled a lot in his young days. And then he finally settled down in La Junta, Colorado. And that is where you met my mother.

02:53 Okay, so we married your mother.

02:56 My dad’s nice married my mother’s brother. And that’s how they came to know each other. And so they married and, and started having a family have an older brother that was born in New Mexico because they traveled back. And then I was born in La Quinta, six years later. And then we moved to Grand Junction, Colorado, where he was working as a as a ranch man. He milked cows for this man. And we lived there until I was about six years old, six or seven years old, and then we moved into Grand Junction, the town of Grand Junction. So from there, my dad was a field worker, because he had no transportation of any kind there for a while until he bought himself a little Model T car. And then and then we we used to, they used to take us kids to pick green beans was quite far out of town. So my brother and I took care of my tiny little brother that was born in 1930. And we stayed in the car all day long waiting for them. They would come to eat lunch and we’d see them for a little while and then they’d go back and pick more green beans until the late evening. Many times the car wouldn’t start and so we had to be there until it was dark. So it so so we had a few times of panic when the car wouldn’t start. And it was getting dark and everybody laughed, except us. So it was kind of was kind of there’s happy memories. Now, at that time, it was just kind of I would say, oh, there was lots of sad things that would happen at that time. And, and I can remember, when we eat lunch, my mother would boil potatoes and, and corn on the cob and boiled eggs that was fun to eat lunch at it at that far out, it was kind of like a picnic every day. We had fun then. And we, we really had lots of good times. I think about it now. And it seems kind of sad that we that we grew up like that, but it didn’t damages any. It was just a lot of fun at that time. But we had no other means of livelihood except my dad working out in the fields, my mother. And I learned to cook when I was 10 years old, because sometimes I had to stay home and take care of my two brothers. While they went out. My mother and dad went out and worked in the fields. And that wasn’t very easy. And I wasn’t too crazy about it. My dad taught me how to make tortillas. And the beans were already cooked from the day before. So all I had to do is make the tortillas for when my mother and dad would come home was lot of Bert once

06:57 you make the tortillas with flour,

06:59 flour tortillas. Yeah, we be in from New Mexico, I guess my dad wasn’t too crazy about corn, or they they ate a dolly, which is corn with milk. And my mother didn’t especially care to cook Mexican things. So she did a lot of we eat a lot of macaroni and stuff like that that wasn’t Mexican. But she liked to she grew up on this farm on this cattle ranch where you didn’t eat a lot of Mexican food, you know, the cooks learn how to cook or they cook biscuits and gravies and, and stuff like that puddings. My mother being a teenager at that time, tried to learn how to cook all that. And she was better at cooking, things like that than Mexican food. So we didn’t need much of that until we came to Idaho. And we came to Idaho in 1942. After we had been to Nyssa Oregon. We came from Grand Junction to Nyssa Oregon in what is called a ring Ghannouchi where they send out kind of scouts and ask if the people want to come and work in the farm work and, and they pay your way. So my dad really thought that was a neat opportunity. So we went to Oregon, we went to NASA and my brothers and my dad and some friends that came with us. They worked. And so my mother and I didn’t have to work in the field. At that time. We had a little sister so my little brother enjoyed working with him, but he didn’t have to work all the time. Robert Robert, and my little sister Eleanor was just four years old. I was already 17 at that time 17 or 18. Anyway, that that I mostly helped my mother and even if we lived in this it was kind of half of a house that we that former provided us with and there was some little other little buildings where the boys slept. And it was Yeah, separate from the house. And we went to the store about once a month I guess when when the land, Lord and his wife went to the stores and we went with them and bought our groceries. And we didn’t have any refrigerator or anything. So we had to buy things that didn’t have any chance of spoiling. So we ate a lot of canned meats and a lot of potatoes. And, of course, we had a huge garden at that time. So it was nice. But the weather was beautiful over there. And then my dad had been in Pocatello, Idaho when he was a young man. And there was only the railroad station. And the rest was really not much of anything. The Indian reservation was where it is now I think, or Fort Hall, because he remembers seeing Indians and, and even talked to some while he was waiting for his freight train, so he could hop it and go back to New Mexico. But he really enjoyed it here. He liked the weather. And he liked the way the people treated them. Because in Colorado, there was quite a lot of prejudice. And so we grew up kind of, I grew up kind of timid anyway, because of that. But my dad always remembered that when he was here that one time that people really treated him well. So and then, of course, this town was just booming with people at that time with the war and, and the air feet airfield out here. And it was just lots of people. And anyway, that, that we came here, my dad and my brothers came first. And they all got jobs on the railroad. And then my mother and my little sister and my little brother. We got here about the day after Thanksgiving in 1942. So we didn’t find a very nice place to live because it was so crowded. But eventually we got a nice house on Fourth Street. And the people here we’re so nice. The word does the SAS whereas the one scientists that really treated us nice, took us under their wing and helped us to get settled. And they were all they were all people from Mexico that had come from Mexico. But we we just got along really beautifully. And there didn’t seem to be to any prejudice with a white people. The Indians went came and went and I was really surprised to see that they wore moccasins and they were their babies in their back on a blanket. The ladies, the men all had long braids. They tuck them inside their shirts. And they spoke a lot of Indian at the time, Indian language. And we it was really something for us to seek as we had never been around. Indians like any way that we settled down and oh, by the year or two later, my brother married a girl that was half Indian and half Irish. And so my dad decided that we would just stay here he had planned for us to go back to New Mexico as soon as the war was over, and he had gathered up enough money and even bought a place in New Mexico. But when my brother got married, he decided that we didn’t need to go clear down there anymore. We just stay here in Pocatello.

14:08 Was that Jose, me again?

14:11 No. My brother Jose Luis, married here at that time. And then my brother had gone into the service came back and 4647 so that’s why they decided to just stay here. And we had met lots of nice people made friends so we just didn’t feel like we wanted to move anywhere anymore. Excuse me, go ahead.

14:44 How did they hide in your family do all the traveling when you came from Colorado and Oregon

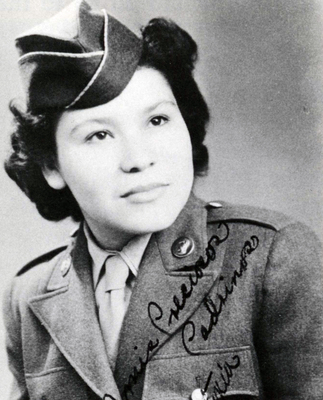

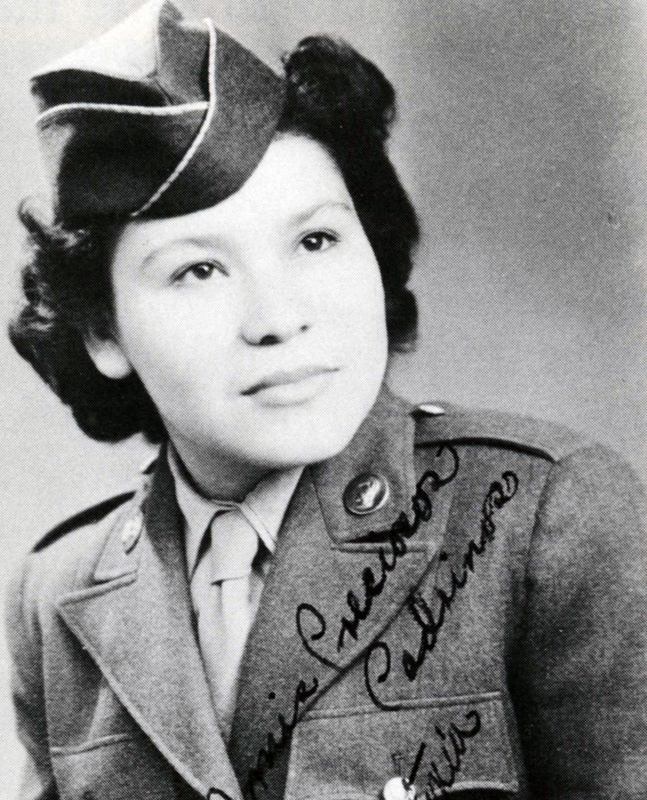

14:50 will have when we went to Oregon from Grand Junction Colorado, the farmer that we that my dad went to work for paid our way it was that was A urangan chair they pay your way to, to go to wherever you’re going to work for these people. So that’s how we got there. They paid our way. We traveled by bus, the Trailway bus. And it was kind of slow. We finally got there and, and then when we came to Idaho, from, from Nyssa, Oregon, we take the train. The trains were just noted at that time, it was really hard to get a seat. It was really crowded with lots of people. And when we decided to stay here, so being that Pocatello wasn’t extremely large we we walked everywhere we went, there was lots of taxis. And remember a bus at that time. It could have been but pretty soon, my brother came back from the service and my second brother was married and settled down. And well, I went to the service to in 1945. I enlisted in the wax and and took training for hospital aid. They call this medical technicians. So we did the cleanup work and we gave some shots. And we we didn’t. We weren’t allowed to give pills, only the head nurse to dad. And that was that I took my basic training in Fort Des Moines, Iowa. That was really something my girlfriend and I enlisted from here. And then from Fort Des Moines, Iowa. We spent six weeks in Fort Sam Houston, Texas. Learning to be medics. And once we were there and and Greg graduated from our training. Myself and five other girls were sent to Hamilton Air Force Base in, in San Francisco, California. I was in only 18 months the war was over by then. And they were replacing us with young men that were coming in on the draft. So I was kind of happy to come home.

17:56 How did your parents feel when you enlisted?

17:59 Well, I think that they were not real, real happy. Because none of us had ever been too far away from home my oldest brother did a lot of traveling to when he was before he went into the service. But I think that me being the only girl at that time. Well, my little sister, but I was grown up. And I think they kind of worried a little bit especially because the women that entered into the service weren’t too popular. For the very simple reason. The man didn’t like it because they said women’s places in the home. They don’t need to be in the army. And, and the people around here, of course, we’re used to things like that happening. And there were only two of us in the Mexican community that went there were others, you know, quite a few others. But as far as the Mexican community we were slightly frowned on, I think. But you but we came back and they accepted us. All right. So and my parents were kind of glad that we had different experiences and learned how to get along with other people other than just here. And I liked it myself. When I came back I enrolled in the at that time we had Rick’s link School of Business. And I attended that for a year and went to work as a waitress. I worked as a waitress for the railroad Beanery what they called it, it was a nice restaurant that was right there at the railroad in the railroad depot. And I really enjoyed it because there was so many people coming back and forth in the trains. I worked midnight shift at one time, and I really, really liked it. When the when the place was full of people, I enjoyed it more. But it was fun.

20:34 Where did you go shopping for groceries or clothes or whatever,

20:40 here in town. There used to be a store. It was home owned by these people. And they were white people. I can’t remember their names. But we used to trade there all the time. My dad and the man got along pretty good, I guess. I don’t know how come they knew each other. But we went there. And we used to trade a lot with credit at the time. Since the railroad only got paid twice a month, I think. And we used to shop there quite a lot.

21:21 So did your dad work

21:22 for the railroad? Yeah, by this time? Oh, yeah. When we, when they first came from Oregon, he got a job right away in the Roundhouse what they call the Roundhouse. And, and my brothers worked in different places in the in the railroad. I worked in the railroad too, for for a while when, before I went into the service. I worked in a place called the the scrap dock. We used to pick up pieces of metal that that were for the for the railroad cars, pick them up from one pile and put them in, in another pile. The good ones, the bad ones, we put on another pile. So it was kind of fun. We worked outside and it was in the summer. So we had fun. My girlfriend and I worked there. And there was a little store on Fourth Street run by Bill in Annie Angelo’s. And that was the teenage spot where everybody came together, we drank more coke and ate more chocolate cupcakes than anybody else. I think we’d get through working at in the railroad, we’d run and take a bath and get cleaned up and come to the store to see who was there. And almost everybody was there all the time, the morale lows. That the and join the Lord is the John was in the service at the time, I think. And all the other kids that were around, I can’t even remember their names anymore. And then when the raw settlers had come into town, well, most of them worked, you know, for the railroad to and rather than in the fields they and that’s really funny. They were they needed a mostly for the ice plant. So that’s where they worked a lot. So they were all young kids to you know, in their 1820s 25 That’s where I met Ernie Flores and I moved for several others, but they’re the only two that I know stayed and and we all had lots of fun. Everybody was at the store is just like the corner drugstore in other towns. Net nets where we talk then giggled and laughed. And, and then from there, sometimes we’d all go to a movie. And there was a lot of fun. And down the street there was another little store run by a little Greek couple, little man named Gus and his wife. They were always trying to teach me the Greek alphabet and how to speak Greek. And their little store was really going downhill. But they were so sweet. And I don’t know. I guess they died. I didn’t really hear any more about him. I don’t even know if they had people here. But they were really sweet. And and they, they were real, real Greek. You know what I mean? They didn’t speak much English at all. And it was kind of fun to listen to him. And then later on of course, the bigger stores, there was the big store called the People’s market. And it was, I guess it was the the next four runner of the supermarket, because everybody went there. Of course, there was a safe way. And I can’t remember what other store there was. Were several others. But that’s where we traded the most. It was also a home owned. Store.

25:43 You said the Mexicans were treated really well here?

25:45 Yes. If there was any prejudice, it wasn’t out like it used to be where I came from, from Grand Junction. In Grand Junction, they even had signs up on the windows, no Mexican trade. And it was really, it was really something you know, when I when we came here, that’s the first thing we noticed, they didn’t have signs up on the windows in the restaurants, no Mexican trade in the hotels, like they did over there. And that’s why my dad liked it better here. He said, People were treated better here. The Indians didn’t seem to be prejudiced against, you know, that the people had any prejudice against them. They walked all over in town, like I said, their babies in their backs on their back and, and they and they they congregated in the different corners, and nobody said anything. They were always there. And that’s the reason why my dad liked it here. So well. Nobody was discriminated against going to find a job at that time. While in Colorado, the only job that the Mexicans could have would be on the on what they call the extra gangs fixing the railroad tracks. And the Italians worked, like the jobs that my dad and my brothers had here. What they call hostile hustlers, and white birds. I can’t remember what they were, what they were called. Anyway, they took care of the engines when they came in, they cleaned them inside and out, washed them. And I helped in that turntable in the Roundhouse to turn the cars around the end the engines. And those those jobs here were all held by mostly Mexicans. And while in Grand Junction, a Mexican couldn’t get a job like that, in the coal chute and all those other places, mostly the Italians work in those places. And, and there, there was, like I said, lots of prejudice. And the Mexican people from here didn’t like the Mexican people from Mexico, the Mexican people from Mexico didn’t like the people from here. And actually the ones that got the jobs on the railroad gang, were the Mexicans from the other side, because they only used to pay a quarter an hour. As far as wages, you know, when so the Mexicans from this side said absolutely not. They wouldn’t work there if that’s all they were going to get. So that’s why mostly they the Mexicans from here, or called, we were called Money dose. And because we were mostly from Colorado and New Mexico, and that’s where we were for they were mostly in the fields, picking teachers, topping nanyan Picking green beans, topping B and failing beets, and picking apples, things like that, you know, if Mexican was lucky enough to be employed by the same employer all the time, that would really be great. I remember my dad walking 11 miles to pick peaches. And like I said, we really were real poor. At the time, we had no transportation. And so when this chance came along the going Rangga and jet to to Oregon, my dad really liked that. So that way we got out of town, better jobs and Uh, well better wages anyway. So that’s, that’s why we came.

30:06 Did you attend school

30:07

here? Well only, uh, when I first when we first came here I was only 1819 43. And so I went to, to ISU and took a course and electricity, because I wanted to be an electricians helper. See they had the gun plant out here. And they used a lot of electricians and lots of electricians helpers, and I only knew very

few people that work there. So I took the course it was six weeks, I think. During the winter, I used to walk up there, my dad would walk me halfway up to the park and then from there, I’d have to work but my walk by myself the hill to the low tech called the waterpark. He’d want you to call Well, no, not the park, the well, the ISU parks, the ASU grounds. And then from there, it would be getting lighter. So he just leaves me there. And I’d walk all the way up the hill to the vote tech, there were only the three big buildings for the road tech. And there were lots of women taking courses as the electricians helper in electricity, and welding. And something else having to do with radio, electronics, I guess it was

31:45 bring to her for

31:46 that. Yeah, they were teaching the women for the, for the war effort, you know that lots of the men were being released to go to into the army. So the women used to, were being used to take jobs over here in like, say in that gun plant. But I never did go to work for the GM plant. Instead, I went to work for the railroad. And then I was 19. And I and that’s when I went to work for the Beanery. And and then, shortly after that, in 1945, I joined the service. And from there then I went to link school of business where I attended a whole year and then like I said, went to work as a waitress again. So I worked in a little Chinese restaurant over here on center. And then I got married. And since in those days when you got married, you didn’t work. You stayed home. That’s what I did. I stayed home and had children.

33:00 So your earliest memories of school though? Your great school

33:05 days? Well, well, they were back in Grand Junction. Yes, I went to school. I remember that. My brother and I couldn’t go to school until after the beet harvest because we didn’t have money to buy us clothes and stuff to start school. So we started in October. I remember that because when my mother sent me with a lunch and, and a tablet, I think. And we walked with a little town called Appleton from from where we lived in the farm in Grand Junction. We lived five miles out of town. And the next community was called Appleton and that’s where the school was. So we walked that way home it must have been a mile or so that we walked and and so they took me in all the kids that were in school. Since I was the new kid, they all crowded around me. And I didn’t know how to speak English. So they thought I was kind of a novelty ears and they and they talk about me in front of me but I couldn’t understand too much. But but when we went in and the teacher said sit around the in the little chairs in a circle, and they handed me a book. And I opened it and I couldn’t imagine what that little bird was doing hanging upside down on that thing until the kids came around and said no, you have to hold it this way. Then the bird was sitting right on the spot. But it was really cute because all those little kids tried to help me. And where I couldn’t speak English, I would just smile, you know, and they all thought that was really neat that I couldn’t speak. There was one or two more Mexican kids that I knew that were there, but they had been in school before, you know. Anyway, I had a beautiful day in school. But the teacher wrote a note to my mother and said, Please not to send me to school until I learned English. So I never went back to school. Nobody taught me and my brother could speak English, he was already in the fifth or in the sixth grade. So, no, nobody ever taught me and I never, I guess I just never asked. So when we moved into town during the bad part of the Depression, I guess it was 1936 or something like that. 37 Something like that. I was already about seven years old, eight years old. And I taught myself to read it to read anyway, my dad had taught me how to read and write in Spanish, but for some reason, I did not connect the Spanish it with the English. Of course, I didn’t have much exposure either. But when we moved into the town of Grand Junction, my mother, we had a, there was this man that let his houses his little houses out, free of rent, to the real poor people. And we only had to gather up a little money to help him pay the water. And he was really nice. And so that’s where we moved because my, my sister’s parents live there and grandparents and they’re the ones that got us the house. Well, we went into this tiny little two room house and my mother said, It was terribly dirty. It was full of smoke inside, you could tell just probably bombs had lived there and cooked in the middle of the floor, and the walls were just full of smoke. But behind the door, there was a great big old stack of Saturday evening posts and call yours magazines. So my mother made some paste out of some flour and water and, and papered the walls with these magazine pages. That’s where I learned how to read and write English. Because I would dope out the letters. And finally at that age, I was already seven and eight years old, I was able to dope out the meanings with the letters that in Spanish that I had learned, took me that long. Anyway, I learned how to speak English and how to read. It was really wonderful because to me, it opened a great big new world to me. And so that’s that that fall, I went to school, and we went to a little school called the Riverside School, it was right next to the river in a nice little there was a park and there was the railroad went right by, and this little schoolhouse only had the for grades first, second, third and fourth. And the library in one room in well, one little building was in one little building. And it was really nice. The teachers were really good. And that’s where I learned how to read better and oh there for a while I was the smartest kid in the first grade. I was eight years old, I was smarter than all of them. I could read speak Read and Write Spanish and read and write English. So that made me the interpreter for the teachers also. So it was really neat. I really enjoyed those four years there. I was such a smart kid. Set math was the thing that that I wasn’t too good at. But the teachers would always tell me if you would, if you would get to know your math better. We would put you a grade higher. But it was too comfortable. I guess for me. It didn’t really matter. But I really enjoyed that. And then Excuse me. Next from there, we had to go to school across town, which was the fifth and sixth grade I had to and that’s where I learned that I wasn’t as smart as I thought I was because the work got harder. And the children were not very friendly. And I was the only Mexican kid in that in the two classes, we had fifth and sixth grade in the same room. And every time the teacher asked me what my name was all the kids turned around and stared at me. And that made me feel kind of bad. She would say, and what is your name Victoria Archuleta. And they’d all turn around and look at me what a funny name. And then, and then, when one day, we had to get up and say, What nationality we all were. So of course, she started with the first row and the second and third when it got to be to me, I said, I was Spanish American, Mexican, Indian. And that caused a commotion. The teacher said, That’s right. That’s what she is. Because Mexicans have Indian blood, and cheese. And they they end Spanish. And she is American. So I was the center of attention for a minute or so. But I didn’t really appreciate it because I was really shy. But it was a good experience, although I was kind of timid and I did feel kind of put down every once in a while, especially when we will had to walk to school with those signs everywhere. And, but it was all together. It was nice. I and then I was in the 10th grade when we moved to Oregon. So I very slyly dropped out of school. And we were in Oregon, my dad said you have to go to school, and I made all kinds of excuses and reasons why couldn’t go. So I didn’t. So after we came here, I went and took that course in electricity. We I got really good grades. And I used to make up some of the neatest connections at home with the lights and the lamps and the radio. So wonder I didn’t electrocute myself. But I did use the really like it. And then I went to Lynx School of Business after I came out of the service. And I got good grades there too. Only I didn’t do anything with them. I just went to work as a waitress.

42:49 But years later than you took the course and child.

42:52 Or the years later, when my let me see I’d had already had eight children. I had always said that when I send my last child to school, I was going to go to school because I wanted to be a teacher. Well, in the meantime, after my my Lucia had six children, and then four years. Yeah, four years later, I had another little boy. And the reason I didn’t go to school after that was because I went to work in the hospital. I worked in what was called the central service supply, and where we work with autoclaves. And we sterilized water in instruments and stuff like that. And since I had been in the service, they asked me to go and work there. I had a friend that asked me to go to work there. So I didn’t pay much attention to going to school anymore. But in the meantime, I had I had had my seventh child, and that may be died. He was two years old and he died. And I was still working in the hospital at that time. So I immediately thought I had to have more children. So I had two more. And so the others had all gone to parochial school. So when I had these other two I didn’t send them to parochial school. We started out in Headstart. I sent my first little girl to Headstart and everybody had to put in 10 days in Headstart at the parents for there to help their children and help whatever so I went in I really liked it. I thought wow, this is the closest to a teacher I’ll ever get. So I after I put in My 10 days I asked the director if I could keep going back. And she said yes. So I did. I kept going back. And when they Lisa, my next to the last child went into the elementary school I had the Laurie at home. So I went with her. And they finally decided to employ me i They started paying me for going so. But I really enjoyed it. And there I took lots of training for you even was able to get a what was it? CDA certified children’s? What? Child Child? Yeah, it had to do with child development. And it was in accreditation. What do they call that? What is that associate? Associate Degree. Yeah. And I got that. And like I said, I really enjoyed I think I worked 15 years that I got paid for 15 years working there. But oh, it was about a year before I retired that I was started working just part time. But they used to call me a lot. They used to call me even after I retired, I went back several times when they needed me. I had asked them that if they needed me, you know, I could go. So I did, I would make my time, work my time around so that I could go and help them. Like I said, I really enjoyed it. But when my husband retired, I retired also. So now I’m just a grandmother and great grandmother.

47:05 I’m gonna back up a little bit, when you were talking about living in that housing place where the man was real nice, and you gave him some money to help you with the one. You mentioned that your sisters parents and grandparents got you in there.

47:21 Well, my my sisters, grandparents had three children, two boys, two girls and a boy. And the reason we met them was because they were sending beats across the road from where we lived in the little farm in Grand Junction where my dad took care of the cows and milk them and all that helped process the milk and, and, and they were working there tapping beats and the boy was the same age as my brother. So he kept going back and forth, taking them water and sandwiches. And then in the evening, he invited them to come over. See he had to they had two girls and one boy, so he was just about 14 or 15. So something like that, anyway, that he brought them over and to meet my mother and my dad.

And so they became really good friends. So we used to go visit them all. every other Sunday, we would go into town and visit them. every other Sunday, they’d come out to visit us at the farm. So we got to be real good friends. And so well the oldest daughter got married and the youngest daughter got married. And and then they all at this time we went to live in Grand Junction in the town. Because the farmer had lost all his farm and everything. During the Depression. He couldn’t pay my dad anymore. So we moved into this little place where they, my my sisters grandparents asked him if we could live there. So we went there. The we lived about about about three yards away from each other. And so we were always constant friends. And when the girls got married, of course they started having children. And each time that the one heard her name, the oldest girl’s name was Patsy. The second one was Ramona and the boy was Gilbert. And the grandmother was Pomo Santa. And the grandfather was Marcial. He was part Navajo Indian. Anyway, that the girls got married and started having children. So Ramona, the second daughter would ask my mother and my dad to baptize the babies while they had one and it died. Then they had another one and it died. And the third one lived to be four years old. But then he died. So they had another new boy. And he was two years old. When my sister was born. When they when they had the baby girl, the mother Ramona was suffering of tuberculosis. And she was very, very sick. And the doctor had told her not to have any more children. Well, she wanted a little girl, all those others that had died were little boys, and the one that was living was also a little boy. So it’s funny that they were such good friends. And one day, my mother said, Oh, I would like to have one more baby girl, because all they had was me. And I was a tomboy. So she said, I would like to have one more baby girl. And of course, at that time, Ramona said, although worry Florentia I’ll have a baby girl and give it to you. Everybody was healthy and well and happy. And they just laughed about it. Sure. Well, it seemed like after all this time, when she did have that baby girl, Ramona was very, very ill. And she was not supposed to have any more children. But since she did have that baby girl, the doctor said that she was not going to make it. And so the baby was 15 days old, when she and her deathbed told her husband, that she wanted my mother and dad to have that baby. And she said, anyway, it’s not going to live very long. The doctor said, and see in the her mother and dad were too old to take care of a tiny baby. Her sister had about six of her own already. And her husband’s family didn’t weren’t able to take care of her. So she wanted my mother and dad to have that baby. So we see, and they named her, Eleanor Vivian. And of course, their last name was carbohydrate. Anyway, my mother and dad baptized her and brought her home with them, but three yards away, brought her home. And then three months later, well, three months from the time the baby was born, the the Mama died. Ramona. I always used to say that when I had when I had kids, if I had a girl, I was going to name her Ramona, too, because I really liked that lady. She used to play paper dolls with me, and she used to teach me how to bake. And she, she sewed beautifully. And she embroidered Oh, she was really talented. And I really was attached to her quite a bit. So I always said that if I ever had a little girl, I was going to name a Ramona. So I did. My oldest daughter, anyway, that they would not adopt the baby, legally to my mother and dad. But when we came to when we went to Nyssa, Oregon, my dad and mom, of course, asked permission taker with them. And then of course, eventually, he got married and had family and he had kept the boy or her brother. And so that’s how come we got a baby sister. I was 14 years old. And my two brothers were younger. And we just doted on that baby. We just spoiled rotten that was all there was to it. She’s 50 some odd years old, and she’s still spoiled. So it was really wonderful for us because we really thought that was neat.

54:04 You’ve done a lot of kinds of work, where you always paid in in money or when you pay otherwise.

54:12 Oh, you mean for when I worked when you work for the jobs you’ve had? Yeah, we got paid. Well, I was on the railroad. Payroll twice because I worked for them out the scrap docks and in the Roundhouse at times. I swept the Roundhouse. And then and then I worked as a waitress in there Beanery. And it was at different times that I did and I was on their

54:45 payroll. Yeah. And your parents got paid. Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. There was no kind of

54:50 tree No. No, and we traded in the stores. Like I said, we had credit in the stores. We didn’t pay money right away. But in Grand Junction also, when my dad worked out in the fields, yeah, they got paid money, they they could take some of the produce if they wanted to. But I remember those great big, beautiful peaches my dad used to bring home. Gorgeous. They were so good. And apples that they bring. Yeah, it was. It was really there, there wasn’t much money, but they did get paid.

55:41 Were there any differences in the way that the men were treated and the women were treated in your jobs, the different jobs you did, um,

55:49 when we first started working in the railroad, there were lots of women working in the railroad already because of the war. But they weren’t treated differently at that time. Because they were needed, I guess, and not. And actually, they it was kind of a half two kind of thing, because they were sending so many able bodied men out to the services and, and there were lots of older men working, you know, my dad was in his 50s and 60s, at that time. And, and they there were quite a lot of older men and women also, like they were not the young ones too. But this railroad here was such a big place and such a central point out here, there was lots and lots of people, lots of workers, three shifts at night. So it was it was quite crowded. Like I said there was the Ross arrows that came in from Mexico and air field out here. And that was it in Nyssa. Oregon was where they had the camp for the Japanese people. You know, they gathered all the jet Japanese Americans and put them in a camp. They weren’t very well treated. But here in Pocatello, I didn’t notice any of that. I understand they had a German camp somewhere. But I didn’t have German prisoners but I don’t know where.

57:53 Who it was just your family that lived in the household or was it? Anybody else? Your grandparents, you

57:59 know, my grandparents on both sides died when my parents were really young. But there were about three boys that came with us from Grand Junction in the same in the say, oh, there was lots of people that came from Grand Junction but three boys that wanted to work with my dad because my dad only had the two boys. And they wanted to work with him. So so they lived with us. I was Felix Gonzalez and his brother piffy Gonzalez. And another boy Oh, there were two others but I can’t remember their names. But the ones that stayed with us yeah, there were were P fi and feelings which stayed with us all the time even when we came to Pocatello so they’re kind of we regard each other as family, you know. They stayed with us all the time.

58:52 And did your dad own his house where he lived in Pocatello?

58:59 Not at first this house he bought. Oh yeah. He had a house up on North third. Yeah, they bought that house right after I went into the service. They bought that house and they lived there until 1955. And then, and then they came and they bought this house. So and that was quite something because my dad had bought some property up in New Mexico and we were going to go back to New Mexico and build a house there. He was going to make a doubt about all of this like everybody else had a house like that. And it was really neat to think about but then we never did go he sold the property. And so he bought that’s when he bought the house here for North by the flour mill.

59:57 So what would you say is the most important thing about Pocatello to you

1:00:02 Well, everybody has an opportunity to do what they want. You know, there’s education. There’s ISU, my brother graduated from ISU and I took classes there are a lot. And like I said, some my grandchildren will be there. My children attended one year each, I think. But the opportunities in Pocatello are. I would say pretty good. Because I always felt that we were pretty well accepted here. And we’re not real, real poor. But we’re maybe we’re not completely middle class either. But we It makes for a pretty comfortable life that we’ve had here. And in case there is any prejudice, we have learned to kind of defend ourselves. We weren’t, we are timid, like we used to be. And I brought my children up that way. When anybody called them names, I would tell them, You tell them Well, that’s alright. I might be a Mexican, but I’m not dirty. And you might even be dirtier than me. But in good words, I never let my children fight. My brother used to get mad at me, because he tells me you’re teaching these kids to be nothing but sissies and not fight that no, that’s not my way. And I don’t want them to fight if they’re going to come up against prejudice because somebody doesn’t like them because they’re Mexican. Well, that’s those people’s problem, not my kids. Because they have been taught to respect other people. And of course, they never lived among that kind of stuff like we did. We used to have people calling us all kinds of names. Of course, we weren’t very nice sometimes either. We’d call them back. So we lived around a lot of Italians. And of course, what we call gringos. But the prejudice was never anything here like it was back there. So this is why we I have always liked Pocatello and and I’m planning to stay here.

1:02:42 In you’ve lived in this, your mother lived in this house.

1:02:45 Yeah, my mother and dad bought this house and the property in the back, which was my house. I raised six children over there. And of course, they had the run of grandma and grandpa’s house. And then when my dad died, my husband and I and my last two little girls came to live in the basement apartment of this house. And we didn’t stay much in the basement apartment. We stayed up heroes, because my mother was alone. And then eventually all

1:03:30 okay okay, so your kids in

1:03:39 Wales might my children all kind of moved out and got their own jobs and had their own places to live in. So there was only the two last ones. It was six big ones and two little ones. And Elissa and Laurie were the little ones. And they were just going to grade school when all the others were grown up already. And eventually, some got married. Like I said, some are still single. And and we lived back and forth with my mother and my sister finally decided she wanted to live in the house in the back where I had lived. So when my mother died, the house was mine, you know, and the little house back there is my sister’s. So we’ve gotten along pretty good and never lacked for anything.

1:04:39 Do you recall any special sayings or expressions that were used in your family?

1:04:44 Oh. Well my mother used to when she would get really irritated at something and she’d say, my lyac and DNS. I don’t What it means, but she would always say that and and the kids always remember her saying CMP and anatra saddles, Komal. Wherever they’ll mirando which was really funny to them, they didn’t understand what it meant, but they still remember it now. And they always tell each other that but oh yeah, my dad had lots of sayings, man something I can’t remember right now what they were but i He was always a real mellow type of man. However, he had a pretty bad temper. Remember that Model T Ford I was telling you about. When night it wouldn’t start, we were clear out in the Hmong, the hills where they had been working. And the car wouldn’t start. And he was so mad. He told my mother bring me the axe. And she went on, she thought he wanted to make a hole underneath the car or something. So she went and got the axe and he took it from her and was starting to beat the car up with it. And she took it away from me No, no. Break the car, how are we going to get home. So he had a bad temper. And he was funny. My children always remember how funny grandpa was he was always making faces and all the stuff aggravating my mother because he acted young. He played with the kids and and he really enjoyed children. And my mother was always to business like she just couldn’t tolerate. If a kid wouldn’t make a mark on the on the wall. She would really get uptight, you know, like writing on the wall like the kids do. And crayons, she would really get aggravated. But my dad didn’t he thought that was cute. And that’s the way I am. I think it’s really cute that the kids leave their handprints on the mirror and all that. What, what about your brothers? Do they still live nearby? Or where do they live? Well, my oldest brother died when he was about 56 years old. He died of cancer, the labor. But he had been in the service and he had worked quite a bit. His name was Jose, Jose Miguel. He used to call himself Joseph Mitchell. But he had kind of a colorful life. When he was 20, he enlisted in the Air Force. And then just a little bit before the war, he went AWOL. And we were always told not to say where he was, although we knew where he was. And we knew that he had changed his name. So he used to write to us all the time and let us know where he was. But since he deserted when, before the war, you know, they didn’t really make too much out of it. I imagine they looked for him. But he was in he was in a town in Idaho named Council when we were living in NASA. So one day we went and picked him up and took him to NASA with us. And then when we came to Pocatello, he enlisted in the service under that same name that he was using was Richard Madrid. And he enlisted in the service. And he went clear to India. And the war was not over yet. And he was in that. And in that district who I can’t remember what they called it. But it was in the middle eastern places. And we have a picture of him there. And he used to send us pictures and lots of little things from India. But the day Oh, he’d been out a month. He’d been out of the service a month when the FBI came looking for him. And things got straightened out there was a little bit written in the paper about it and that was it. He put in his time anyway in the service. So they like As they pardoned him and my youngest brother, my, my, yeah, he was two years younger than myself. And that’s Jose Luis. He died in in industrial accident in, in Boise in 1967. He already had three, but he had five children. He had divorced once and married again. So he has five children that he left in his oldest son Louis works to work in, down in Florida and in California with NASA program. And and the second one lives in Fort Hall. And I don’t know what he does. He was a fireman there for a while. And third son works as a reporter and radio announcer. And right now, I think he’s working in construction. I’m not sure. I don’t see them very often. And the other two from the second wife live in Nampa. My niece is an inhalation therapist, and she works in PE at type D. And the brother I don’t know what he does. I think he works for traded company. He saws wood and kind of like a carpenter, I guess, I really don’t know. But that’s his family. My oldest brother never married, so he never. And then my youngest brother went to ISU graduated as a teacher. And he taught from the first grade up, I think up to the sixth grade. And then he went to work for the University of Utah. To tell you the truth, I don’t really know what it is he did. But now he’s retired and he’s counseling. He’s doing a lot of counseling to the, especially the Mexican people, or the Mexican students that that are having a hard time in school. He helps them. And then for the longest time, he worked in that Weather Center teaching English to the people that came in from Mexico, Puerto Rico, and even Chinese and Laotian people teaching them English. And he’s had a very full life in, in education. And he’s still enjoying it. And my sister, since she was very sick leave when she was born. He has always been kind of sickly. And right, recently, she had been quite ill. So, but she lived, they said she wouldn’t, but she’s 51 years old. So like I said, everything’s been pretty good for us. Our children are all working. And I just love my grandchildren. You have family reunions, about every year every two years we have family reunions with my husband’s family because our family we there’s only three of us. Of course we have many relatives in Colorado, my mother’s one brother had six children. So we but we have never been real, real close. And all of those kids are in education, also music into music. So but we don’t like I said we don’t know them really well.

1:14:21 Do you have some customs and traditions that your ancestors had? I mean cultural kinds of thing.

1:14:30 Um, well, whenever we have too, too many green chilies we string them up in a restaurant like they did in New Mexico. My dad taught us how to do that. And you see I have one my brother brought me but and we use a lot of Chile Colorado and and we eat a lot of tortillas only we make them out flour. We don’t use the corn an awful lot. But I remember when we were younger, my mother and my dad used to make pies out of prunes and raisins. Everybody around when I tried to make one for my children, no way do they like them, but we loved them. And of course down in New Mexico that’s about the only fruit they could preserve during the winter. They dry apples and dry plums and raisins and stuff. Of course, I don’t know if they raised their own or what I know they they had that kind of fruit during the winter and they made guesses from milk and they drank a dolly which is the dried the dried corn and then they grind it into a fine powder and they mix it with milk and boil that and put cinnamon in it and it’s delicious. I tried to feed that to my kids and they don’t like it. But we did and we one custom from from New Mexico that my dad always used to do is cook the beans with dried corn. He would soak the corn and clean the beans and put them all together in a in a in a bucket and then dig a hole outside in the dirt and set a fire in in it and then take out all the cinders and put the beans the bucket of beans and cover it with a moist sack and then put dirt over it. And all those beans would be delicious by the evening. And if he had a little sore salt pork he put in him those beans were so good. And of course here and he would cook corn that same way that corn on the cob, leave the the husks on it and build a whole hole and take out the fire afterwards and just put them in the hole and cover them up with lots of wet gunny sacks and then put a tarp on it and put dirt on it. We tried that once we burned it all was awful. We had bought a whole gunny sack full of corn and we were going to do what grandpa did with it. The corn husks were burnt to a crisp in that corn tasted awful. But those were cooking customs that they had. And then of course the Christmas holidays when we were young, weren’t celebrated anywhere near like people celebrate now. The way they used to talk they would make plays and Posadas. And they had a play that make called last month touchiness. And according to the way they said they had, it was quite a pageant and very colorful. They, they, they, they would oust Satan out of heaven and throwing to the ground. And then they would have skipped that would talk about why and my dad used to remember all of those lines, and he used to recite them to us. And so it was really fun to listen to him, but we never saw it. We never saw it when we lived in Grand Junction. Nobody did anything like that. The only thing we did that they taught us was that we go from house to house and say nice Christmas. And they would give us all kinds of goodies at each door they’d be prepared. Mostly the people from Colorado because the people from Mexico didn’t know that. Well no, no, I it might have been

1:19:47

a splinter from that because see we’d go from house to house but we didn’t say anything other than this Christmas. And people would open the door for us and they I either feed us there or give us goodies to take home. I remember they, they used to give us little in binary TAs and put away laws. And I told him

if we would come in, give us that doorway and no candy, Christmas candy. So it was fun for us them. However, it didn’t last very long because we got too big and we didn’t do that anymore. But he was kind of like trick or treat here. But oh, they’re nice memories, you know. And another thing that my parents did a lot when it was done in in Grand Junction a lot was to have the Laureus and they would rig up an altar in the corner of the room. And this is where my sister’s mother when she was young, she just used to love to decorate that altar, my dad would make the altar and her dad would help and they would put linen, linen scarves on it and then decorated without, with crepe paper. And then they would bring all their images that they had, you know, they’re statues of the Virgin Mary and all the others. Lots of them had different ones, big ones and little ones. And they from the neighborhood, they bring all their statues. And then they would spend the night the evening and the night praying the rosary. And, and singing. I love Bibles. They call them. I just used to love to hear them. And and then they would take a break. And then they’d come back and say another rosary and more songs. And then at midnight we’d feed the people. And there was always chi Ling na. What else did they feed them? Oh, beef roast, I guess roast beef, and Chile, Colorado in the US and WinUAE laws. And lots of the people will get together and bring in food. And the one thing we never had was tamales or enchiladas because we didn’t know anything about them. You know, the people from Colorado at that time, didn’t have that influence from Mexico, I guess. Mostly because we never got long. The people from Mexico didn’t like the people from Colorado and New Mexico at that time, didn’t get along at all. So I remember that. And then at midnight, everybody would go home. And after they be in and it was always really nice. I really enjoyed it. I was just a kid, you know, and I really enjoyed that. I really liked to hear the singing. And lots of people knew those songs. I never heard them in church. But

1:23:34 these millennials, were they for a week a week. Yeah, there person.

1:23:38 No, no, they were just celebrating the saints celebrating. The fact that they were Catholic, I guess I don’t I don’t know that was an old a very old fashioned tradition. Because after I was about, well, when we came to Oregon, I was 17. Like I said they hadn’t had them for a couple of years or so within maybe five years. Nobody had too many more.

1:24:14 When did they have them? Oh, how

1:24:16 long the time when I was about 789 10. But I

1:24:22 mean, what time of the year? Was it any season or?

1:24:27 I don’t remember that. I don’t remember if it was anything probably. Well, All Saints date is in October, isn’t it? November, November, November? Maybe it was then I don’t remember. Because everybody used to bring their statues and put them on that altar and they’d make flowers and

1:24:52 did they have more than one time a year?

1:24:54 Um, no, I think they did it once a year. That might have been the case would have been I don’t remember. I’ve never heard of that before. Yeah. And like I said, they made those probably once a year and the Met the, the community of the people that were from Colorado, you know that money that they would come from all over to come to those audios.

1:25:24 So Religion was pretty important to your family.

1:25:27 Well, I imagined so they made us go to church, and three night and all that we Yeah, my dad, well being that they were raised out in the farms out in the ranches, away from the churches. They didn’t get mass, but once a month. And so I think they were kind of used to that. Because my mother and my dad, I don’t remember, they attended. They attended church in the holidays, and whenever we had what they called me Ceylon, they would send to a priest that spoke Spanish, and we’d have the whole church to ourselves. We’d have the whole church to ourselves, and they even teach us Spanish hymns. And I really liked that I really enjoyed it. I learned a lot more of the, of the Catholic religion during those times and I did in English. For the when I was young, you know, and of course, we always went to catechism. And my brother, Jose Miguel went to parochial schools until he was about 15. But I never got to go because we were too poor. By that time, they didn’t. They couldn’t afford to send me and my brother Louis. So we went, that’s when we went to the local area. Public Schools. Yeah. But religion didn’t play quite a bit. My mother used to say her novena, pretty often. Law novena, there’s Santonio, and her. Oh, and I can remember when we lived out in that farm, my brother’s Padrino baptism, he was an old sheep herder. And he’d come to stay with us in the winters. And, and he would have us every night we kneeled and prayed the rosary and said, the Stations of the Cross no matter what. And me and my brother Louis would be. And my dad would go like we are. And my mother had a rug on that front room where we all kneeled that was made out of straw was real pretty. But all that was hard on the knees. It was so hard, we get up and we had all these ridges over knees. And, and he his name was synovial. And he had us praying and praying and praying and we’d get so sleepy. It was just my me and my little brother that my oldest brother prayed only if he felt like it half of the time, he was goofing off, but but me and Louie had to sit, kneel and pray right next to my dad. And if we were looked like we were even gonna whisper to each other he, He’d have us. But, yeah, when he came, and he was there, every winner every week, until we moved to town. He left my dad a big book called lie storia sagrada, and he had taken some deer skin and put a cover to it. And just until this spring, when my brother Robert was here, I gave it to him. It’s been here all alone. And well, my little brother was born in 1926. So we’ve had it since then. So my brother I took it to him. I thought he might like to read it, but I doubt it. Maybe I’m just asking for it back. He ideas.

1:29:34 So tell me a little bit about what you did to socialize or pass your free time. Oh.

1:29:41

When we were little. We used to go to the different farms where they would celebrate birthdays, and they give less money and eat us as a serenade. And we go, my dad would borrow the the wagon from his employer. It was a huge, about as big as this maybe bigger as the table. And my mother would put blankets and pillows in it. And my dad and her would ride in the in the seat, you know, seats that bounce up and down. And they hitch two horses to it. And me and my brother would be laying in the back looking at the stars. Oh, it was nice. And they take us to the next house. They pick up neighbors and and there was this one lady her name was Sam us piano lesson your essay was Deanna and her husband, Don Pancho. And he played the guitar and she sang beautifully. You could hear that woman singing all over the whole valley, I think. And to sing less money. Anita says eautiful boys that just used to fascinate me. And her husband had a great big old white moustache. It was huge. And he would pay like guitar like this. He put the guitar up like this. And he’d play and she’d say, Oh, I just love to hear oh, we must have been about a nine. Oh, no, not even that old yet. Six. What I did six years old five. And she was the one that made the mindless. And that’s how we got acquainted with tamales. Although my mother never made them, never made them. So in our teenage years, when we lived in town, we didn’t eat Terminus. But that lady was the one that made them and she makes sweet on my list with raisins in

them. Are they delicious? And this one time we went to celebrate somebody’s birthday, they lived in a town called Loma and we stayed there I think three days. Are that was fun. The ladies made cakes they made what what’s that called? With the bread and the raisins. We Don’t Die that Oh, that was good. And they made all kinds of meat, all kinds of vegetables. And one of the daughters which was younger, made beautiful cakes. With chocolate frosting on we had never had such a wonderful time. And we like I said we stayed there three days, they had a violin and the guitar and they danced until the wee hours of the morning. Everything was so nice. You know, there weren’t any discrepancies in anything really everybody. And some of the people were from Mexico because when we lived in the farm, I told you across the road from us, these people that came from Mexico lived there, and we got acquainted with them. And my mom and dad got acquainted with them and, and they used to have these fiestas in their house. And eventually when my little brother was born, they baptized him and had a great big Fiesta for that. And and I remember that’s the first time I had ever eaten pineapple. And I guess since they came from Mexico, they were used to having that type of fruit we never I had never seen it my mother and dad probably knew about it but I didn’t. me see. I was born in 24. Robert was born in 30. That meant I was four years old. Okay, that’s what he was baptized. I was just for my brother was to and and they had for dessert. They had pineapple in little plates. I thought the most delicious stuff I had ever eaten. They didn’t fix it up in any way just out of the cam. And that was just wonderful. Oh we had eaten all kinds of canned fruit my dad my mother used to be you know since they were more or less a eight more green gold style than Mexican. We ate beans and potatoes and macaroni like I told you we eat a lot of macaroni and meat. Chicken my mother always made chicken soup and stuff like that. But when it make came the making

- Title:

- Victoria A. Sierra

- Date Created (Archival Standard):

- 10 January 1991

- Date Created (ISO Standard):

- 1991-01-10

- Description:

- Interview with Victoria Archuleta Sierra.

- Interviewee:

- Sierra, Victoria Archuleta

- Interviewer:

- Luckey, Angela

- Subjects:

- Mexican American family life farming (activity or system) group identity ethnicity armed forces racial discrimination communities (social groups) railroad workers education Spanish (language) Hispanic American

- Location:

- Pocatello, Idaho

- Latitude:

- 42.8615307

- Longitude:

- -112.4582449

- Source:

- MG491, Hispanic Oral History Project Interviews, University of Idaho Special Collections and Archives

- Finding Aid:

- https://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:80444/xv327325

- Language:

- eng

- Type:

- record

- Format:

- compound_object

- Preferred Citation:

- "Victoria A. Sierra", Hispanic Oral History Project Interviews, University of Idaho Library Digital Collections, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/digital/hohp/items/hohp037.html

- Rights:

- In copyright, educational use permitted. Educational use includes non-commercial reproduction of text and images in materials for teaching and research purposes. For other contexts beyond fair use, including digital reproduction, please contact the University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives Department at libspec@uidaho.edu. The University of Idaho Library is not liable for any violations of the law by users.

- Standardized Rights:

- http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC-EDU/1.0/