Episode 14 : Naturally-Occuring Fire : an interview with Bob Mutch Item Info

In this episode, titled “Naturally-Occurring Fire,” Bob Mutch tells us how changing fire management in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness led the way for new practices in wilderness all over the United States. Bob Mutch retired from a 38-year career in wildland fire research and management with the U.S. Forest Service in 1994. In the mid-1950s, he worked as a Forest Service smokejumper in Missoula, MT. Bob later served 11 years as a Fire Behavior Analyst on a national Type 1 Fire Management Team. A highlight of his career was the development of the first Forest Service Plan to allow wildland fires to burn in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness to restore an important natural process. Bob holds a Bachelor of Arts in Biology and English from Albion College in Michigan and a Master of Science in Fire Management (M.S.F.) degree from the University of Montana. In 2007, in acknowledgement of his ongoing accomplishments in the national and international wildland fire arenas, Bob was presented with an Honorary Doctoral Degree in Forestry from the University of Montana.

In this episode, Bob relates the story of the first wilderness “let burn” policy, beginning with his involvement in the fire study of the Whitecap Creek area of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness.

Episode 14 : Naturally-Occuring Fire : an interview with Bob Mutch [transcript]

00:00:00:00 - 00:00:29:11 Debbie Lee: Welcome to the Sawai Bitterroot Wilderness History Project, which is made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The University of Idaho and Washington State University part of the project’s mission is to collect, preserve, and make public oral histories documenting the history and people of the South. Bitterroot Wilderness. For more information, please visit our website at SPW lib argue idaho.edu.

00:00:29:13 - 00:00:54:11 Debbie Lee: And then I think people, I think people get so much out of being in a wilderness setting. Once you take away cars and money and telephones, people are different and they are different to each other, I think. And, and, and then they draw on things in themselves that maybe are a little rusty from our crazy life out here.

00:00:54:11 - 00:01:25:14 Debbie Lee: Now, I think the ways that people get along when they’re isolated in a place like that, that they place that they want to be, are really it’s a wonderful thing.

00:01:25:17 - 00:01:52:07 Debbie Lee: Thank you for joining us for the 14th episode of the Selway Bitterroot Wilderness History Project. In this episode titled Naturally Occurring Fire, Bob Mutch tells us how changing fire management in the subway Bitterroot Wilderness led the way for new practices in wilderness all over the United States. Year. Bob much retired from a 38 year career in wildland fire research and management with the U.S. Forest Service in 1994.

00:01:52:10 - 00:02:14:29 Debbie Lee: In the mid 1950s, he worked as a Forest Service smokejumper in Missoula, Montana. Bob later served 11 years as a fire behavior analyst on a national type one fire management team. The highlight of his career was the development of the first Forest Service plan to allow wildland fires to burn in the South Bitterroot Wilderness to restore an important natural process.

00:02:15:01 - 00:02:50:26 Debbie Lee: Bob holds a Bachelor of Arts in Biology and English from Albion College in Michigan, and a master of Science in Fire Management degree from the University of Montana. In 2007, in acknowledgment of his ongoing accomplishments in the national and international wildland fire arenas, Bob was presented with an honorary doctoral degree in forestry from the University of Montana. In this episode, Bob relates the story of the first wilderness lit burn policy, beginning with his involvement in the fire study of the white Cat Creek area of the South Bitterroot Wilderness.

00:02:50:28 - 00:03:01:18 Debbie Lee: Was the white Camp study area. Was there a fire there already or no. Or did Bud. Why did bud. Yeah.

00:03:01:20 - 00:03:27:07 Bob Mutch: It’s interesting. Yeah. I guess could have been anywhere in this region. And I guess it was partly chosen because there are there are landforms and vegetation types there that are represented through much of region one of the Forest Service in the northern Rocky Mountains. We had open ponderosa pine savanna, pine trees and grass. We had North Slope, grandfather dug for lodgepole pine communities.

00:03:27:14 - 00:03:57:15 Bob Mutch: We had South Slope, Doug fir, ponderosa pine. Doug for communities. We had a large area. 54% was in the subalpine type. That high elevation country. We love to back back in. Last year, granite rock and open vistas and subalpine fir and whitebark pine. And so it had it all. And, the bitterroot. The other feature on the bitter is they had a forest supervisor that this was in a casual interest.

00:03:57:15 - 00:04:24:15 Bob Mutch: He he wanted it. I mean, when you talk to Orval Daniels, you know, this was really important to him just from a philosophical standpoint for good land management that it’s not right to suppress a natural process like fire in a wilderness where fire has been molding the landscape for eons, for thousands of years. So it had a good it had a good person to host it in Orval.

00:04:24:18 - 00:04:48:20 Bob Mutch: It was it was nearby, you know, some good fire facilities like the fire lab and forestry sciences laboratory were some good research support nearby. And, everyone agreed this is this is a good place to do it. It also had a good this is important too. You wouldn’t want to pick an area that never had any fires. And especially if you’re going to allow lightning fires to burn, you know, you’re right.

00:04:48:20 - 00:05:15:25 Bob Mutch: They have a lot of lightning fires to burn. And the records have been looked at and lightning caused more than 90% of the fire starts back 45 years were started by lightning, so it was a natural outdoor laboratory if there ever was one. Both from a human standpoint, people committed and interested from a vegetation standpoint and from a meteorological standpoint that the lightning source was there.

00:05:15:25 - 00:05:39:06 Bob Mutch: And indeed, whenever plan was approved, we would have fires, and we had the plan approved, we would talk more about it a little bit later. But the plan was approved two years later. The fires, the study started that year and 70 pretty well presented. The plan of the chief for the Forest Service, John McGuire, and his staff and July of 72, two years later, we had a plan.

00:05:39:06 - 00:06:05:29 Bob Mutch: It was about that thick, and it had all the do’s and don’ts and the criteria and how we manage fire and which fires we might put out. And and so the chief, almost on the spot in Washington, DC, and we were all sitting around a big table is very formal and just Orville and I, we gave him a briefing, and John went around the room and asked all of his staff what they thought of this, and and not everyone was in accord.

00:06:06:00 - 00:06:07:05 Debbie Lee: So were you nervous?

00:06:07:05 - 00:06:29:13 Bob Mutch: Yeah, I was a little nervous because he was so well-respected in the Forest Service circles. And but we went around the room and he raised our a little bit. And of course, I briefed Orville, and Orville was able, you know, to cover the wilderness base as well in the briefing before we even had opened up the discussion. And and when I went around the room, I think this guy said a few things.

00:06:29:13 - 00:06:56:18 Bob Mutch: But, yeah, John McGuire before his over said, you know, I like the sounds of what we’re doing and, and, and we’re going to give you our verbal approval today and you’ll be getting our, our final formal approval very quickly. And I just say that because two weeks later, my daughter and Linda and I, as early August, we were back in the wilderness doing some more vegetation work, and I got a call on my Forest Service ranger on his Hamilton Dispatch through a repeater.

00:06:56:18 - 00:07:19:14 Bob Mutch: And they said, Bob, we’ve just had a new lightning fire over and bad luck right here we are two weeks old on the planet. We had a fire and they said, we want you to hike out to Paradise, and we’re going to have a helicopter there. And not maybe not the best from a wilderness standpoint, but they were treating it as an emergency, partly, and we could use helicopters for emergencies.

00:07:19:14 - 00:07:37:15 Bob Mutch: And we said there’d be a helicopter there, and we’re going to take you over and and drop you off, and we want you’re on the ground assessment of this fire. We’ve sort of tentatively decided it, one that should burn. But we want you to take a look at and report back before we give it our final approval. So I was dropped off.

00:07:37:15 - 00:08:00:22 Bob Mutch: I mean, it was 24ft by 24ft. It was another like my Handy Creek fire, another nothing fire, another one of those lightning strikes in a snag and burning in a shrub field. And in four days it never got beyond 24. By 24ft. And it went out. And I mean, it just went off. And there was a lesson there to that.

00:08:00:24 - 00:08:23:16 Bob Mutch: Sometimes our knee jerk reaction that every fire is a bad fire. Well, maybe, maybe not. And in wilderness most likely not. And so I, I had to say I didn’t need the helicopter and they just continued on that other business and it wasn’t that far. And I hiked back down to the Selway and up to Paradise and to the cabin where I’d left Linda for the day.

00:08:23:16 - 00:08:45:14 Bob Mutch: And, and talk to, Esso and Dispatch and Hamilton. And it was our first fire. I mean, it was the, Yeah, it was the bad luck fire. Yeah. The very first fire was in Bad Luck Creek. And and some thought that that wasn’t a very good name, but, for our very first fire. But it turned out.

00:08:45:16 - 00:08:52:18 Debbie Lee: Well, what did you guys learn then, in that, how long were you on that project that study?

00:08:52:19 - 00:09:15:17 Bob Mutch: Yeah, we. You always started 70. A little introductory deal. Get acquainted, gotten the project area 71. The rest of the 7071, 72. We’re doing all the field work. We did fire history work to learn about the frequency of fires, like in the fire scars and ponderosa pine. That that keeps fire scars intact going back 2 or 300 years.

00:09:15:20 - 00:09:53:27 Bob Mutch: And we learn like people learn everywhere in Ponderosa pine, from Arizona, New Mexico to Montana and Idaho, all that in ponderosa pine because of the flammability of the needles and the fire behavior. And in ponderosa pine stand, the fires occur on the average of about every 10 or 15 years, and there was that periodicity, frequency of fire about every 10 to 15 years going back, say, 2 or 300 years all the way up to about 1900, 1910, 1920, when the Forest Service moves onto the scene and starts putting fires out.

00:09:54:00 - 00:10:20:16 Bob Mutch: And there’s an unbelievable marked decline in fire scars and ponderosa pine from that time forward. For decades, we kept fires out of, plant community, where fires were part and parcel of the health of that community. And so we did fire history work. We did fuels work. We did fire behavior. We did, we had some, hydrologists come in and do some stream work.

00:10:20:23 - 00:10:53:15 Bob Mutch: After one of our fires, we had, the fisheries, think she was, she was either master’s or PhD student at the University of Montana. And she came in and and did, a post-fire aquatic insect survey within the, the Fish Creek fire downstream from where it started, in upstream, where there was no fire effect in about 4 or 5 miles of the riparian zone, it burned pretty intensely in the fire that summer of 73.

00:10:53:17 - 00:11:43:14 Bob Mutch: And and she did a pretty detailed study of was there any measurable effect of, really heavy burning on aquatic insects above, in and below the fire and and her conclusion, as I remember it, is that aquatic insects recolonize so quickly that she really couldn’t detect any anything of significance. And we did a soil, morph on a morphologies, do some landscape work, identifying the various, landscape types and these four of these five vegetation zones I described to you earlier, shrub field, the pine savanna, south salt north slope and subalpine, those became and then finally you get all of this information and you think, wow, you know, what does all this mean?

00:11:43:14 - 00:12:01:27 Bob Mutch: What’s I mean, what are we going to do? We’ve got to have at some thread. We have to have some continuity. When it came down to putting the plan together, we had all these all these pieces of data and all, all kinds of stuff. And we started and we laid it all out on these five geographical, ecological land units.

00:12:01:27 - 00:12:29:21 Bob Mutch: We call the values ecological land units, landform and soils and vegetation pretty much defining physically and biologically what’s there and what its capacity is. And fire and metal and fire behavior was different, obviously, in the subalpine, where, you know, it’s long winter, short summers, not very productive, not a lot of plant growth, not a lot of fuels over time like there is in, north north slope, more moist community.

00:12:29:24 - 00:12:55:09 Bob Mutch: So fire behavior fuels, fire history, natural breaks due to rock formations and things like that all kind of fit together like pieces in a puzzle. And we decided to put it all together and we we suddenly realized, well, we can be very, liberal up here. And a 54% that’s subalpine. It’s high like that. So it’s quaking.

00:12:55:11 - 00:13:26:07 Bob Mutch: And they drew a line at 7000ft. So since that everything above is free to pretty much do, what it wants to do is some limitations. And so the pieces fit together in in the Doug fir, ponderosa pine South Slope unit, where we identified frequent fire and then no fire. we realized that in there a lot of latter fuels in the absence of fire, a lot of Douglas fir groves, that would have been killed by those fires every 10 or 12 years.

00:13:26:12 - 00:13:54:28 Bob Mutch: Fires? The stands were not as open as they would have been historically. There’s more fuel. There is enough more fuel and a crown fire potential where the typical historical fire would have been, low intensity surface fire because fires burn so often, there wasn’t a lot to burn if you’re burning every ten years. So we realize that we had the most effect through fire suppression on that South Slope ponderosa pine, Douglas fir unit.

00:13:55:00 - 00:14:22:19 Bob Mutch: And we were most concerned of in our prescriptions there, meaning that we didn’t allow any fire starting at the beginning of the fire season to burn there. We just put in a we put in more or less a calendar day. So if it was late in the fire season and we didn’t have months, we just had weeks maybe left in the fire season before the weather would start in late August, early September.

00:14:22:22 - 00:14:45:25 Bob Mutch: There, at that point on the calendar, we would begin to evaluate those fires with a thought that we could allow some to burn gradually. Getting to the point as we have fires over time, or you wouldn’t have to draw those kinds of, conclusions and be that conservative anymore, which we which we didn’t do after a while. So the pieces fell together that way.

00:14:45:28 - 00:15:11:03 Bob Mutch: It was fun to put it together. Seemed to make sense. Most of the people that we talked to thought it was a good idea. Not everybody did. There is a Western one. I wish I’d brought a copy of that journal with us, but there’s a Western wildland, you know, it’s one you really I could send you if you really wanted to see it, but it was a special journal put out by the University of Montana Forestry School, and they covered different issues.

00:15:11:03 - 00:15:41:26 Bob Mutch: I think it was quarterly. This particular issue was a fire issue, and it was after our Fist Creek fire of 73 that this came out. And I had an article in it titled I Thought Forest Fires Were Black. One of our field assistants came in two weeks after his girlfriend came in two weeks after the fire was over and, in the shower of ponderosa pine needles, some of it natural fall needle drop.

00:15:41:26 - 00:16:05:29 Bob Mutch: Anyway, Ponderosa pine, you know, drops the older needles every fall, but some of it was scorch needles coming down. And this surface of that ponderosa pine savanna area that the trail goes up through to bad luck Lookout. The whole forest area that had been black two weeks earlier was now a golden mantle of pine needles. And she hiked in there with us.

00:16:06:05 - 00:16:27:09 Bob Mutch: We’re going off the trail to the lookout tower, and she said to Tim, this is Tim. I thought forest fires were black should these are golden. And in fact, there was such a carpet of golden needles that if someone if there had been an ignition source, you could have had another fire over this mantel of golden ponderosa pine needles.

00:16:27:09 - 00:16:44:18 Bob Mutch: Two weeks after the first fire went through that. See, and but anyway, that was one article, but more has an article in there, and Orville Daniel has an article in there all talking to this experience of the change in philosophy and thinking of the Forest Service torch fire.

00:16:44:18 - 00:16:54:29 Debbie Lee: So where was the, white cat study, program? It kind of first, then.

00:16:55:03 - 00:17:26:24 Bob Mutch: It really was. It was the pilot project and the Forest Service one, as you know. Now, the Park Service had preceded this effort by two years, getting their Park Lightning fire plan approved in 1968. And, that was partly due to the Starker Leopold report. Starker was that professor at UC Berkeley who who wrote kind of a white paper for the Park Service and you’re you should be managing for the natural processes and the natural system.

00:17:26:24 - 00:17:54:00 Bob Mutch: Suppressing fire was one of the most unnatural things you could be doing. That was their impetus to get them going. Our impetus was the Wilderness Act of 1964. That but more of bill war for so instrumental. He wrote kind of the the guidelines on how the Forest Service would implement the Wilderness Act. He was called back to Washington to write the regulations that directed the Forest Service.

00:17:54:00 - 00:18:16:09 Bob Mutch: From that point forward, how well implement the Wilderness Act and Forest Service wilderness. So he was he was a student of that act and and of course, but he had the vision for fire needs to be on the land that remove from the wilderness and Oroville the dedicated for a supervisor and what he Dave and I’d go in the ground for 2 or 3 years in a row.

00:18:16:16 - 00:18:47:23 Bob Mutch: And to answer the rest of your question, there we were two years later, had your approval. July 1st, small fire that August 72nd. Next year, a big fire started in July of, I think it was July or early August 2nd 73. The Fiske Creek Fire and then, we continued some of our monitoring evaluation work. I stayed kind of tied to the effort, probably through the rest of 73, 74, 75, working on the fire lab.

00:18:47:23 - 00:19:09:19 Bob Mutch: Dave was somewhat still involved on the beta of just kind of keeping tabs on on what was going on in there. So it was. And now it’s to the point where, you know, it was just like a brush fire that started in the Bad Luck Creek brush field in 72, allowed to burn and like brush fires do with the ideas, right?

00:19:09:22 - 00:19:25:06 Bob Mutch: This germ was well fertilized and pretty soon the whole cell. We had a plan piece by piece. First it was white cap and then it was Moose Creek. And then it was, up on the Clearwater Park.

00:19:25:08 - 00:19:26:29 Debbie Lee: Do you mean like the most creek.

00:19:27:01 - 00:19:57:08 Bob Mutch: Creek district was added later? the whole district went under a plan. The rest of the Bitterroot and the westward district went under a plan. So the Bitterroot was kind of piecemeal where, you know, once this got on, then, you know, the heathen wilderness in New Mexico and the Boundary Waters Canoe Area was another one to follow shortly afterward, to the point now where I would imagine most large wildernesses in the Forest Service have a wilderness fire management plan.

00:19:57:10 - 00:20:12:15 Debbie Lee: So the conclusion that I’m drawing is that if wilderness were to go away, then let burn policy would go away, and that would be a really, a big loss for the environment.

00:20:12:17 - 00:20:40:14 Bob Mutch: Part of the story. We haven’t told you to answer the rest of your question. the thing that’s interesting about Wilderness fire is that it was so right for wilderness that it has been exported outside wilderness, and we are using it in large tracts of land where we can have a plan to allow fire to burn outside wilderness to achieve other benefits, not the wilderness resource benefits.

00:20:40:14 - 00:21:14:28 Bob Mutch: Maybe it’s wildlife, maybe it’s hazard reduction, maybe it’s esthetically, desirable to have some fires. Maybe it’s to sustain plants and animals outside wilderness that are fire dependent. And, so there have been some really good examples of extending this idea to lands outside wilderness as well. So that’s one lesson that we learned and apply. There’s another lesson that I don’t think any of us, none of the original five ever envisioned when we started this snowball rolling downhill.

00:21:15:00 - 00:21:52:07 Bob Mutch: But this would be an outcome, and it’s a very, very satisfying outcome to the program. And what we’ve discovered now that we’ve allowed fires to burn, year after year, decade after decade, for 33 plus decades now under all kinds of weather conditions, all kinds of fire behavior conditions from from low to moderate to high to very high, even to extreme fire, danger conditions, if the conditions are right, we have had some fires burning wilderness.

00:21:52:10 - 00:22:34:06 Bob Mutch: Even then, those fires burning under every conceivable kind of weather and fuels and topography have left this a legacy on the landscape. Some have called it, I think one was Penny Morgan at, University of Idaho, who’s such a good fire ecologist. She calls it a fire smart landscape, meaning simply this that now we’ve learned, finally, that when we allow a fire to burn in 2004, 2005 or 2006, those fires are being self regulated by previous fires that have been allowed to burn in the landscape.

00:22:34:09 - 00:23:12:20 Bob Mutch: In other words, Mother Nature has has been rolling the dice now so long in the Selway Bitterroot, the fuels have been broken up into such a mosaic of recent, sort of recent, not so recent, 30 years ago, recent fuel mosaics and vegetation situations that now when we have a fire, a fire of this year is going to burn into a fire of some recent past, the fire behavior is going to change drastically, and the fire may not go out, but it’s going to change dramatically in character and where we used to be concerned.

00:23:12:25 - 00:23:31:15 Bob Mutch: And we still should be concerned about a fire burning across the wilderness boundary into lands outside wilderness and causing unwanted effects. We don’t want that to happen, but the fires are sort of taking care of themselves now, which is a to me, a wonderful footnote to this whole story.

00:23:31:18 - 00:23:34:04 Debbie Lee: It is.

00:23:34:06 - 00:24:01:08 Debbie Lee: Thank you for joining us for this episode of the Selway Bitterroot Wilderness History Project, which has been made possible by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the University of Idaho, and Washington State University. The project coordinator is Debbie Lee, recorded and produced by Aaron Jepson.

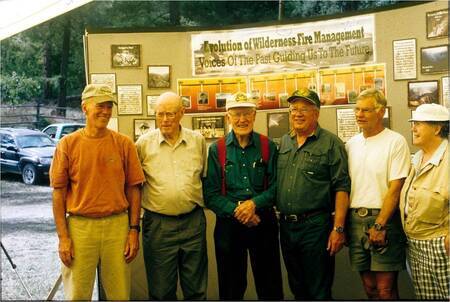

Gallery

- Title:

- Episode 14 : Naturally-Occuring Fire : an interview with Bob Mutch

- Creator:

- Debbie Lee; Bob Mutch

- Date Created (ISO Standard):

- 2011-04-14

- Description:

- Interviewee: Bob Mutch | Interviewer: Debbie Lee | Location: Missoula, Montana | Date: April 14, 2011 | In this episode, titled 'Naturally-Occurring Fire,' Bob Mutch tells us how changing fire management in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness led the way for new practices in wilderness all over the United States.

- Subjects:

- podcasts firestudy fires conservation fire policy

- Section:

- Wilderness Voices

- Location:

- Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness (Idaho and Mont.)

- Publisher:

- Wilderness Voices, The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project, https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/

- Original URL:

- https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/2011/11/08/naturally-occurring-fire/

- Source Identifier:

- Selway-Podcast-ep14

- Type:

- Sound

- Format:

- audio/mp3

- Language:

- eng

- Preferred Citation:

- "Episode 14 : Naturally-Occuring Fire : an interview with Bob Mutch", The Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness History Project, University of Idaho Library Digital Collections, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/digital/sbw/items/sbw296.html

- Rights:

- Copyright: The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project. In Copyright - Educational Use Permitted. For more information, please contact University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives Department at libspec@uidaho.edu.

- Standardized Rights:

- http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC-EDU/1.0/