Civilian Conservation Corps in Idaho Collection

A collection of maps, images, and documents pertinent to the history of the CCC in Idaho

Contents: The CCC in Idaho | Tech

Please note: materials in this digital collection are not held by University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives. Additional information or higher quality images may not be available. Please consult each item’s information to find the holding institution.

The CCC in Idaho

On an evening in March 1933, newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt sat at a table in Washington D.C. surrounded by some of his new cabinet secretaries and drew a simple diagram on a scrap of paper for a visionary plan to rebuild lives and restore blighted natural resources. In a few strokes, he laid out what was to evolve into the most popular and widely dispersed of the New Deal programs: The Civilian Conservation Corps.

The nation was facing the worst economic crisis in American history. One in four wage earners were unemployed, and hundreds of thousands of men of all ages had taken to the road in search of work. Four years after the 1929 crash, the commodity-driven economies of rural America were at a standstill, revealing the crushing human cost of the worse economic depression in modern memory.

While the Dust Bowl has come to represent the epitome of human-caused and naturally occurring events of the Great Depression, the rural West covered a much greater area and affected a much larger population. Coming on the historical heels of overcutting, overgrazing, soil depletion, farm closures, and catastrophic forest fires, by 1933 much of the rural West’s economy was in ruins.

In Idaho, the per capita income of the state had dropped in half, among the lowest in the nation and similar to other western, commodity producing states.

Announced at F.D.R.’s inaugural on March 4, 1933, the CCC was created by executive order on April 5, 1933. With its extraordinary promise to restore millions of acres of devastated forests and other exhausted public lands, it was crafted to provide temporary work and training for young men and immediate relief from the catastrophic effects of the Great Depression on their families.

Idaho was quick to respond. Seeing enormous potential benefits to his state, the newly elected Democratic governor C. Ben Ross sent well-known forestry figure Harry Shellworth and Idaho Secretary of State Franklin Girard to Washington D.C. to negotiate Idaho’s share of the new program. Their energy and expertise won out: the state eventually secured the largest number of CCC camps per population in the United States and the second largest number of any state after California.

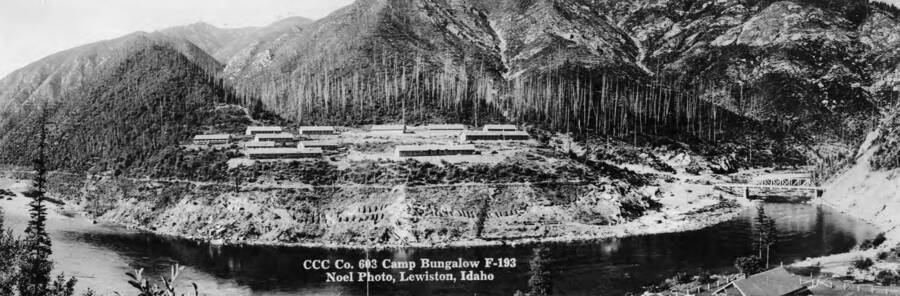

It all happened very quickly. The first CCC camp in Idaho was in operation two months later, on June 6, 1933. Camp Prichard, located on the North Fork of the Clearwater River, was the first installment on what grew to 87,000 enrollees assigned to hundreds of Idaho camps over the program’s lifetime.

As hundreds of CCC camps were built in 1933 across the West and tens of thousands young men poured in to man them, the program stimulated local economies with demand for goods and services and became a significant factor enabling the U.S. Forest Service and other agencies to undertake, for the first time, an ambitious plan to restore and conserve vast tracts of public land in the West.

To be selected, enrollees had to be unmarried, between the ages of 17 and 25, willing to assign $25 of their $30 per month earnings to support their destitute family, and be fit enough to serve, although nearly all were under-weight and lacked high school diplomas, job training, rudimentary health care, or adequate clothing.

At training camps, they received a medical exam, vaccinations, dental care, and two sets of clothes and shoes. They were introduced to basic Army routines that they were to follow for their six-month enrollment period. Under the watchful eye of military officers from 5 p.m. to 8 a.m., and of supervisors for government agencies during the day, men learned how to work and live together.

Thousands of CCC camps were established across the nation, employing three million enrollees to restore depleted and degraded forests, streams, and soils. In the process, the CCC helped shape the environment, rural communities, and economies far beyond the time of its official existence.

In December 1933, the first Idaho camp of the newly created Indian Division (CCC-ID) was created at Fort Hall Reservation, followed shortly by camps at the other three Indian reservations in Idaho. The camps had their own programs that provided work opportunities and training for young tribal men who lived on the reservation while they worked on projects primarily near home.

During the blistering summer of August 1934, a ferocious and unpredictable fire blew up, pinning down fire crews in remote, perpendicular terrain while testing the training and endurance of 2,479 CCC enrollees who fought the blaze over two months. Two Illinois enrollees died in the consuming Pete King-McClendon fire when they were crushed by a fallen tree. Enrollees built thousands of miles of fire trails and hundreds of lookouts, but they also were trained to put out every new fire by 10 a.m., according to the new national protocol, in hopes of preventing fires like the Pete King from burning out of control.

On October 9, 1934, new enrollees of Camp SP-1 arrived on the gentle shores of Lake Chatcolet in northern Idaho to build Idaho’s first state park, named after former U.S. Sen. Weldon B. Heyburn, ironically a staunch critic of the New Deal. While learning carpentry and stone masonry, enrollees constructed the chalet-style lodge, covered stone picnic shelters, overlooks, and recreational trails from local materials in the rustic style common to CCC projects in the northern Rocky Mountains.

In late 1934, the boys of Camp Thorn Creek F-56 finished the Brundage Mountain Road to the lookout overlooking McCall, enabling the creation of the Brundage Mountain Ski Area. Similar CCC work facilitated the opening of ski areas at Sun Valley and Bogus Basin, as well as the construction of the North South Ski Shelter at the Palouse Divide in partnership with Washington State College.

Responding to an increased interest in the American wilds, the National Geographic Society in 1935 launched a party of explorers, scientists, and documentarians down the torrents of the Salmon River. One of the first public research venture into the wildness of the West, the expedition visited Camp French Creek, where CCC enrollees chipped away at sheer basalt cliffs to build the Salmon River Road. This ill-conceived attempt to drive a road along the legendary River of No Return, would have bisected the largest wilderness area in the lower 48 state but instead was determined impractical and too expensive to finish.

On the Fourth of July 1935, enrollees of Camp Moscow proudly marched in the city Independence Day parade down Moscow’s Main Street. As the first Soil Conservation Camp in Idaho, SCS-1 planted locust trees to break the wind on the ridges of rolling wheat fields, protected streams, created nurseries, and demonstrated contour farming techniques to hold drifting soil in place. Deeply eroded gullies and barren hilltops in previously nutrient-rich volcanic soil on the Palouse testified that the living matrix of the fertile West was disappearing due to poor management.

A complaint by black enrollees about mistreatment at Camp Osborne in June 1935 took place at the end of an experiment to place black enrollees in integrated CCC camps throughout the country. Although black enrollees constituted ten percent of the enrollee population nationally, the racial prejudice of both white enrollees and white townspeople pushed the CCC to transfer black enrollees to segregated camps in the South and California. Idaho’s three integrated camps were closed. The black enrollees at Osborne were dismissed from the CCC and sent home.

In October of 1935, the enrollees at Camp Minidoka finished building canals on the expansive Minidoka Irrigation Project. The role of CCC enrollees in extending that water system is evident throughout southern Idaho, where they often manually laid the riprap stones, built livestock ponds, and scratched stock trails from scorched southern plains that supported ranches underpinning the Snake River Plain economy.

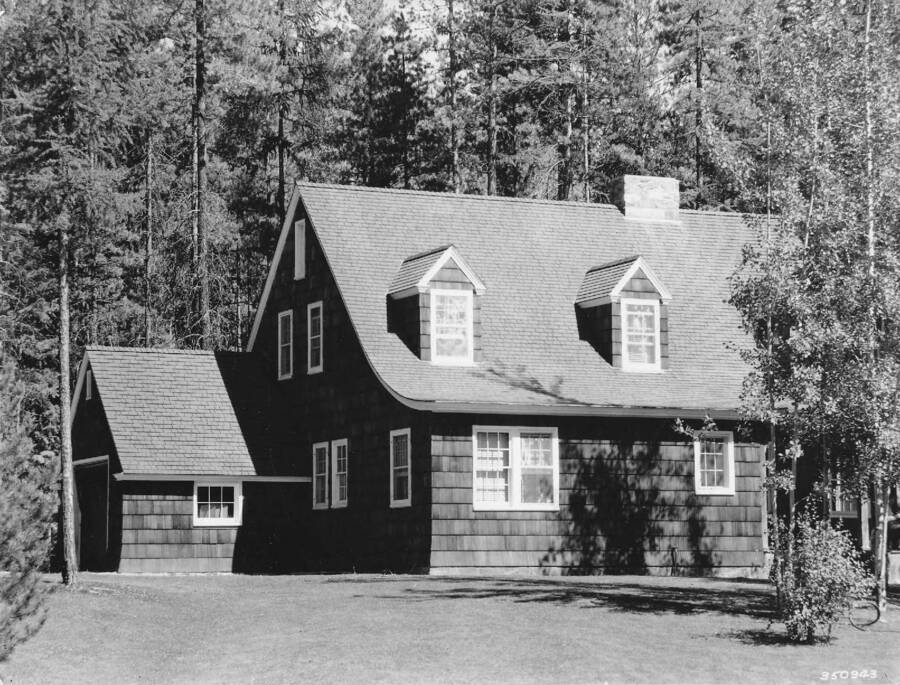

The Priest Lake Experimental Station was a cornerstone of the U.S. Forest Service’s efforts to apply science to understand forest environments for the purpose of restoring and replanting forests. Starting in 1935, the CCC rebuilt the Experimental Station in North Idaho, that sought methods to control diseases and pests devastating native stocks of White Pine.

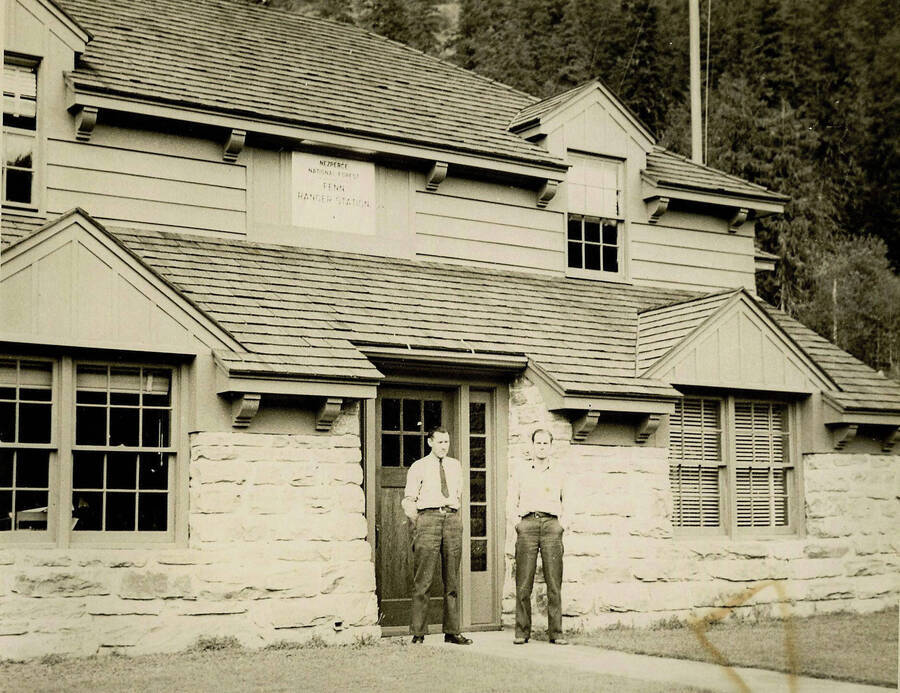

The Fenn Ranger Station on the Selway River, constructed using local timber and stone in conformance with official policy to blend their buildings into their environment, was built by enrollees from Camp O’Hara beginning in 1935 under the experienced supervision of Local Experienced Men (LEMS). The result remains a living testament to the CCC emphasis on aesthetic values and craftsmanship of buildings intended to last.

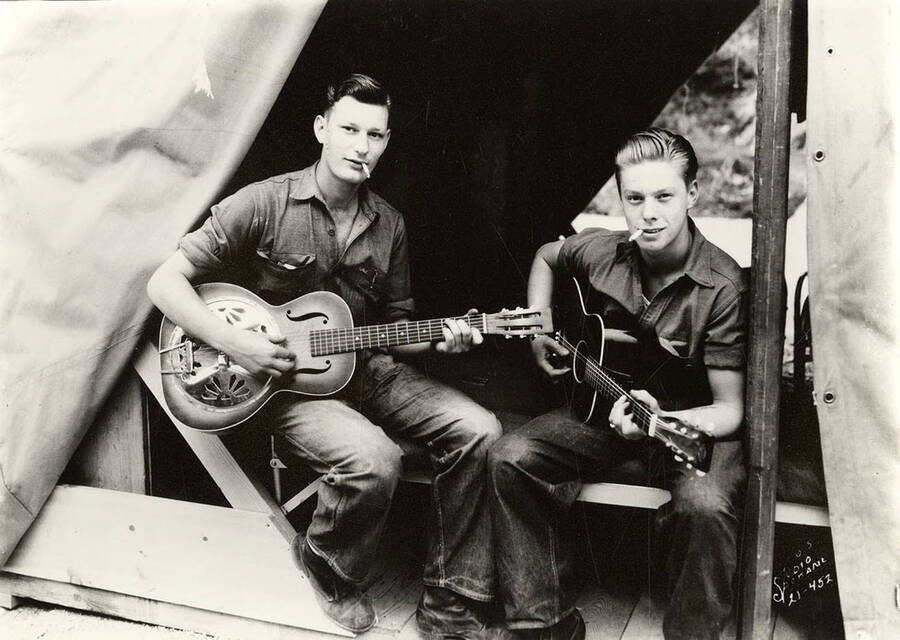

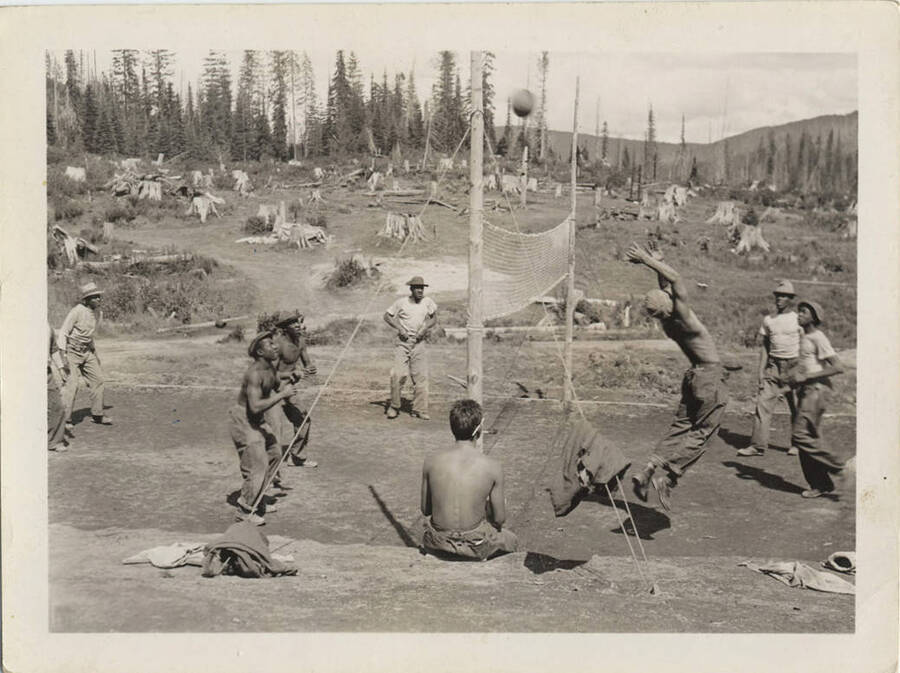

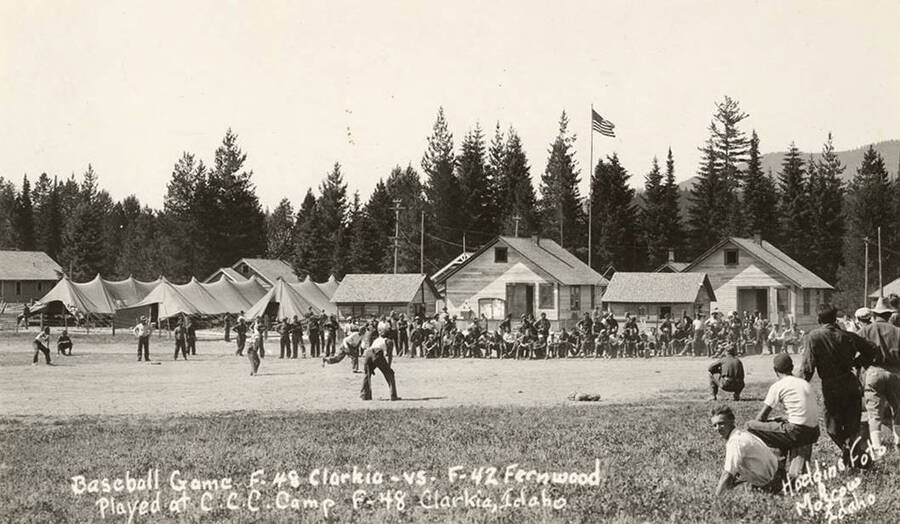

The number of camps and enrollees in the CCC peaked in the nation and in Idaho in 1936. Most camps had 200 enrollees at any one time and were located near their worksites, often many dirt miles from towns or villages. Enrollees spent their monthly $5 spending money in these nearby communities and used free time to practice for competitions against other camps and local teams in baseball, basketball, and boxing.

Communities, at first curious and even hostile to the idea of outsiders coming to their area, usually became accustomed to seeing them at work and then became CCC boosters. Economic benefits were tangible in terms of goods and services provided to camps. One Palouse farmer, for example, made a business out of feeding the camp’s slops to pigs that he then sold back to the camp.

Travelers along the remote Magruder Road today can thank the enrollees of Camp Deep Creek who finished the road through the wildest parts of Idaho on July 16, 1936. First with pickaxes and shovels and then with bulldozers, CCC enrollees built roads, trails, and bridges in remote areas, paving the way for economic and recreational development. By opening the backcountry, the CCC also incurred the wrath of wilderness advocates who decried road building that introduced automobiles into natural areas in the West where they had never been before.

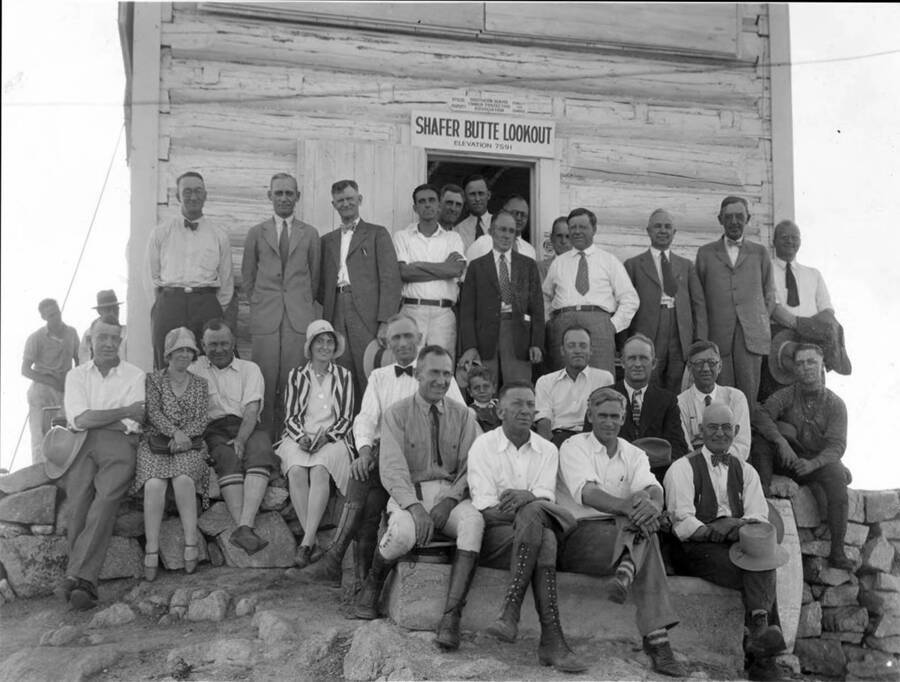

Harry Shellworth was a Republican advocate for the CCC from the very beginning. He also used his influence to create CCC partnerships to support commercial interests, especially by arranging for CCC camps to build lookouts for the Southern Idaho Timber Protective Association (SITPA), which he headed. In 1937, CCC Camps McCall and Smith’s Ferry finished two stunning SITPA compounds, which were designed by Finnish foremen using a distinctive log joining technique.

In July 1941, enrollees bent over radio parts at Lake Fork as part of a national policy shift toward national defense and preparedness. When the CCC was moved to Federal Security Agency in 1939, CCC enrollees could receive training potentially useful should the United States formally enter the Second World War. The CCC initially reflected sentiment against military training due to a desire to stay out of another European war, and training for combat was never allowed in CCC camps. However, hundreds of thousands of young men had learned military-style discipline and teamwork from their time in the CCC and were prepared physically and socially when the time came. When the United States did enter the war on December 8, 1941, many of the new NCOs were former CCC enrollees.

The Civilian Conservation Corps was officially closed June 30, 1942, following the United States entrance into the Second World War.

Technical Credits - CollectionBuilder

This digital collection is built with CollectionBuilder, an open source framework for creating digital collection and exhibit websites that is developed by faculty librarians at the University of Idaho Library following the Lib-Static methodology.

Using the CollectionBuilder-CSV template and the static website generator Jekyll, this project creates an engaging interface to explore driven by metadata.