Episode 8 : Wilderness Photography : an interview with Dick Walker Item Info

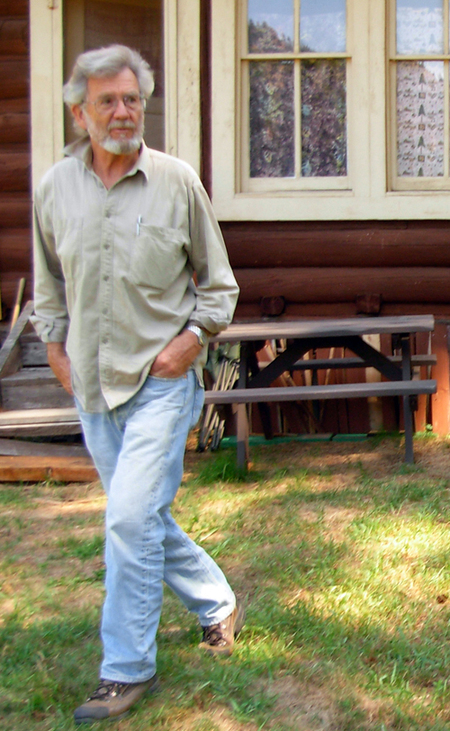

In this episode, titled “Wilderness Photography,” Dick Walker shares some personal experiences with this watershed, and the fish and wildlife of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness. Dick began as a wilderness ranger on the Moose Creek Ranger District, starting in 1969. While there, he began applying the results he gained from his Master’s thesis “Photography as an Aid to Wilderness Resource Inventory and Analysis”. During the past 40 years, Dick continued incorporating both aerial and terrestrial photography to capture the seasonal moments: from winter ski trips, to all season backpack and private float trips, always searching for the historical connection, documenting Nature’s ever-changing wilderness ecosystems, as well as identifying misuse or overuse of the Wilderness Resource. Dick has also turned many of his stunning backcountry photos into an art that brings forth the sustainable fragile beauty of the untrammeled wilderness. In addition to serving as a Wilderness Resource Assistant, Dick was a Wilderness Planner and Team Leader on a Congressional Wilderness Study. He’s also a backcountry pilot and is still flying fire patrol, as well as promoting wilderness values while living sustainably.

Episode 8 : Wilderness Photography : an interview with Dick Walker [transcript]

00:00:00:00 - 00:00:26:13 Debbie Lee: Welcome to the Subway Bitterroot Wilderness History Project, which is made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The University of Idaho, and Washington State University. Part of the project’s mission is to collect, preserve, and make public oral histories documenting the history and people of the subway. Bitterroot wilderness. For more information, please visit our website at SPW Lib argue.

00:00:26:13 - 00:00:28:27 Debbie Lee: Idaho. Edu.

00:00:29:00 - 00:00:53:27 Debbie Lee: And then I think people. I think people get so much out of being in a wilderness setting once you take away cars and money and telephones, people are different and they are different to each other, I think. And, and, and then they draw on things in themselves that maybe are a little rusty from where? Crazy life out here.

00:00:53:27 - 00:01:24:26 Debbie Lee: Now, I think the ways that people get along when they’re isolated in a place like that, that they place that they want to be, are really it’s a wonderful thing.

00:01:24:29 - 00:01:57:25 Debbie Lee: Thank you for joining us for the eighth episode of the Selway Bitterroot Wilderness History Project. In this episode, titled Wilderness Photography, Dick Walker shares some personal experiences with this watershed and the fish and wildlife of the South Bitterroot Wilderness. Dick began as a wilderness ranger on the Moose Creek Ranger District starting in 1969. While there, he began applying the results he gained from his master’s thesis, photography as an Aid to Wilderness Resource Inventory and Analysis.

00:01:57:28 - 00:02:30:18 Debbie Lee: During the past 40 years, Dick continued incorporating both aerial and terrestrial photography to capture the seasonal moments, from winter ski trips to all season backpack and private float trips, always searching for the historical connection, documenting nature’s ever changing wilderness ecosystems, as well as identifying misuse or overuse of the wilderness resource. Dick has also turned many of his stunning backcountry photos into an art that brings forth the sustainable, fragile beauty of the untrammeled wilderness.

00:02:30:21 - 00:02:47:09 Debbie Lee: In addition to serving as a wilderness resource assistant, Dick was a wilderness planner and team leader on a congressional wilderness study. He’s also a backcountry pilot and is still flying fire patrol, as well as promoting wilderness values while living sustainably.

00:02:47:11 - 00:02:56:23 Debbie Lee: Can you talk a little bit about how you got interested in photographing images and turning them into artwork?

00:02:56:25 - 00:03:38:22 Speaker 4 I think at first it was the objective was to document, and it was a little later. I remember going to a taking leave and going to an Ansel Adams presentation at, WSU. And I remember I got there early and it was in one of the auditoriums and, Ansel came in and and sat down midway down on the left side, and I went up and and introduced myself, and, when I reached out to shake his hand, he withdrew his hand and he said, gently, man.

00:03:38:22 - 00:04:10:17 Speaker 4 He said, I’ve got arthritis. It wasn’t until just recently that I understood what the hell he was talking about, because, I, I’m starting to get the reflection myself, so I, but anyway, that was my first. I never got to attend one of his workshops. This was as close as I got, but that it was at that point, and he was using, 35 millimeter, Kodachrome for his presentation.

00:04:10:19 - 00:04:39:01 Speaker 4 And, you know, all of his, his, primary work was, eight by ten format negative camera, black and white, primarily. he did some Polaroid work later on, but I guess maybe that’s where it first. Or like Wallace Stegner, where, you were doing more than documenting. You were trying to capture, sense of place, and, which Ansel did very well.

00:04:39:01 - 00:04:50:24 Speaker 4 And, so did so many of those early photographers with the F 64 club or whatever, where they were shooting for maximum depth of field. But anyway, that’s,

00:04:50:26 - 00:05:17:13 Debbie Lee: Well, there’s one photo in particular set of photos, a remnant of what once was, and I know that they took place in 2001, and they’re based on an experience you had with, Sarah Walker. Can you just tell us about that experience and how you happened upon that scene? And, and, kind of tell the story of that.

00:05:17:16 - 00:05:25:02 Speaker 4 yeah, there were a number of sequences, but I think the one that you’re referring to was early that spring.

00:05:25:04 - 00:05:26:15 Debbie Lee: And what spring 2002.

00:05:26:15 - 00:06:03:06 Speaker 4 Thousand and one. there was a tremendous, totally abnormal in contemporary terms, flush of spring Chinook salmon. And coming up, the, the, the snake and then the Clearwater. And that was the first, spring Chinook salmon I had ever caught. I was with Steve Pettitte, close friend. So we caught these, spring Chinook. And of course, you could keep them.

00:06:03:06 - 00:06:33:09 Speaker 4 And these were hatchery fish. They did not have the adipose. And then later that year, Sarah and I flew in and we were on up this major drainage that flows into the Selway. I had first been on that drainage the fall of 1969. and I was heading up, toward the Montana border. I’d seen this, the set of pools.

00:06:33:11 - 00:06:59:18 Speaker 4 I even had took a photograph or two. And it was a beautiful place pictorially. But when Sarah and I were up there, the place was filled with these giant spring Chinook salmon. Now, these are salmon that are like, two and a half, two, almost four feet long. And they all had their adipose fan. these were wild.

00:06:59:20 - 00:07:28:29 Speaker 4 these were a remnant, truly, of what once was. And this is probably the most intact hydrologic watershed left in the at least the anadromous fisheries part of the Pacific Northwest. so it’s not a question of, well, the habitat support the fish. It’s the freaking dams that are are screwing up the fish. It’s not the habitat, the lack of habitat.

00:07:29:01 - 00:08:05:19 Speaker 4 There was, one fish that I called Whitey. There’s, I don’t know the correct terminology. Steve can clarify that, but when the fish are going down stream in the spring of the year, when they go over the dams, they get something called nitrogen fixation or something. And they’re affected at that point in time. But it doesn’t raise hell with them until two or 3 or 4 years later when they head back up into the freshwater.

00:08:05:19 - 00:08:37:21 Speaker 4 When they first enter the freshwater, then they start losing big patches of skin and stuff. And Whitey had lost all of the skin and the eyes on his head. And how in the hell that fish got all the way up through all those major rapids, including Selway Falls, and then all the way up to Selway and I mean, it did it by sand and something the hell we we can’t even relate to, but it made it there.

00:08:37:21 - 00:08:54:04 Speaker 4 And I have closeout photos of that because, of course, he couldn’t see me. And I’ve got photos that where it was only six feet away, where it was swimming, totally oblivious to me, but it it knew it was it was waiting.

00:08:54:07 - 00:09:16:23 Debbie Lee: So I know that you have a tremendous collection of historical papers and photographs. how did you get interested in the history of the survey? Bitterroot wilderness? are there any historical stories that you that particularly stick with you as being really important?

00:09:16:26 - 00:09:42:17 Speaker 4 I guess initially the history of the place didn’t have very much import or meaning to me. I was more interested in the, the physicality of it. And my comparison was with the, the ray wall, which I had only made a fall trip into in the Mountain Circle wilderness. There were a number of old mining claims and stuff.

00:09:42:17 - 00:10:18:24 Speaker 4 So you know that, you couldn’t go by an old mine and not, not realize that something had gone on there. Well, in the Selway, you didn’t have those kinds of, physical impacts. And two years before I came in, the Forest Service had purchased what was called at that time, the Mush Creek Ranches. It was a complex of, I believe, about seven homesteads up there.

00:10:18:26 - 00:10:57:05 Speaker 4 Anyway, the structures that were on those places, either had been burned incidentally or on purpose. All except for a few that, weren’t right in your face, so to speak. And, in the Forest Service, people didn’t know they were there or they didn’t pose that much of a, an assumed, dilemma with, wilderness resource. Anyway, on the more field trips I went on, the more I began seeing blazes that were not Forest Service, not the heel toe Forest Service blaze.

00:10:57:08 - 00:11:23:02 Speaker 4 And these blazes might be, rather than 4 or 5ft above ground level. They might be ten or maybe 15ft above ground level. And they’d be these, notches cut in the trees. And if the tree was a green tree, this what had been a later, Martin sap cut in with a notch. I mean, so it was like an undercut on a tree.

00:11:23:02 - 00:11:43:18 Speaker 4 You were getting ready to fall the top of the arch on a green tree. It sort of rounded over, so it looked like a cathedral arch. And I was wondering, what in the hell are these cathedral arches? And I’d follow this. This. I’d get off the Forest Service trail and I’d be fallen. Most of these were along the ridge line and then they’d drop down.

00:11:43:18 - 00:12:09:29 Speaker 4 So. And usually where they dropped down, you’d find either a cabin or the remnants of a cabin. So these were the old trap lines and stuff. And so that was my first. That was my teaser. And so I began looking more and more and more. And I remember my first encounter with Jimmy Renshaw. I had come up from Baron Hill and was walking up wounded Doe Ridge.

00:12:10:01 - 00:12:32:04 Speaker 4 and of course the trail then was it was not a mainline trail. And in fact, some places when you’re going through the the ferns, the bracken fern, big, heavy, you could feel the trail with your feet. You couldn’t see it because the bracken fern was so friggin thick. So you’d go along the trail feeling the tread with your feet.

00:12:32:06 - 00:13:01:20 Speaker 4 And, anyway, I was around tribulation, the saddle, someplace like that, and I saw some stock, and I went down and and traced down the the brand and so on, and, and, a couple days later when I got to Fish Lake and I was going up behind fish like, well, I, I came on to this camp and this, this Jimmy Renshaw fella was there, he mentioned, he said, I remember him saying something like that.

00:13:01:20 - 00:13:40:07 Speaker 4 Well, I wondered whose man sign I saw. And so I knew I was talking to somebody who had his feet on the ground and his eyes open. So, And Jimmy was the first person that told me about the possibility of Hudson Bay cabin being downstream and above the meadow complex. at Fish Lake, there. And and I remember seeing the trail, I mean, this cabin early on, and it had a stone fireplace in it, so I knew it was an old, old cabin.

00:13:40:08 - 00:14:07:05 Speaker 4 There was a another cabin that was down on the, below the trail toward the meadow complex there. And it had a punch roof. and you could see along the edge, where they had dug out the earth right along the edge of the cabin and covered the roof for insulation. And of course, that, made it so that the roof was one of the first things to rot on this cabin.

00:14:07:07 - 00:14:24:19 Speaker 4 As the year and I, I took some core samples of the, lodgepole pine right there, and I, I don’t remember they were around 50 years old or so. So, so anyway, that cabin was somewhere between 65, 70 years old or older.

00:14:24:21 - 00:14:26:24 Debbie Lee: And this was in 19.

00:14:26:26 - 00:14:50:27 Speaker 4 that would have been probably 70, 69 or 70. What would be my guess? Somebody like Jim knew the country or somebody like Arnold Oswald or Park Wolfenbarger those individuals knew segments of that country much deeper than any of the rest of us will ever know.

00:14:51:00 - 00:15:18:02 Debbie Lee: Thank you for joining us for this episode of the Selway Bitterroot Wilderness History Project, which has been made possible by the National Endowment for the Humanities. The University by Tahoe, and Washington State University. The project coordinator is Debbie Lee, recorded and produced by Aaron Jepson.

Gallery

- Title:

- Episode 8 : Wilderness Photography : an interview with Dick Walker

- Creator:

- Debbie Lee; Dick Walker

- Date Created (ISO Standard):

- 2011-03-07

- Description:

- Interviewer: Debbie Lee | Interviewee: Dick Walker | Location: Moscow, Idaho | Date: March 7, 2011 | Topic: Wilderness Photography | In this episode, titled 'Wilderness Photography,' Dick Walker shares some personal experiences with this watershed, and the fish and wildlife of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness.

- Subjects:

- podcasts photography

- Section:

- Wilderness Voices

- Location:

- Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness (Idaho and Mont.)

- Publisher:

- Wilderness Voices, The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project, https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/

- Original URL:

- https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/2011/06/15/wilderness-photography/

- Source Identifier:

- Selway-Podcast-ep8

- Type:

- Sound

- Format:

- audio/mp3

- Language:

- eng

- Preferred Citation:

- "Episode 8 : Wilderness Photography : an interview with Dick Walker", The Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness History Project, University of Idaho Library Digital Collections, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/digital/sbw/items/sbw290.html

- Rights:

- Copyright: The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project. In Copyright - Educational Use Permitted. For more information, please contact University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives Department at libspec@uidaho.edu.

- Standardized Rights:

- http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC-EDU/1.0/