The First Black Graduate - Jennie Eva Hughes

by Michelle Shannon

Jennie Eva Hughes (Smith) was the first Black student to graduate from the University of Idaho (Class of 1899)!

Jennie was born on July 20, 1877 in Washington D.C. Not much is known about Jennie’s father, Alexander Hughes, but it is known that her mother, Louisa, married Lewis E. Crisemon shortly after Jennie was born. Like many Americans during the 19th century, including thousands of Black Americans, the Crisemon family left the eastern and southern states and migrated to those of the Midwest and Plains in the decades immediately following the Civil War. Their first stop was in Pennsylvania, where Louisa and Lewis had their first child together, Gertrude. Their second stop was in Oklahoma, where the U.S. government had opened the Indian Territory to settlement by non-Indians. Many Black Americans pooled their land parcels and founded all-Black towns. While in Oklahoma, a second daughter was born, Lousinda.

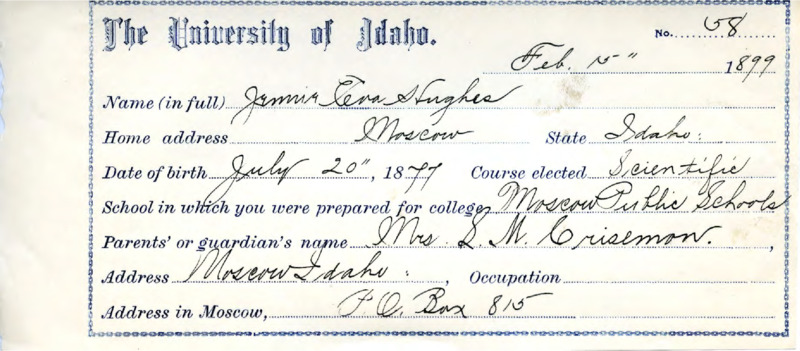

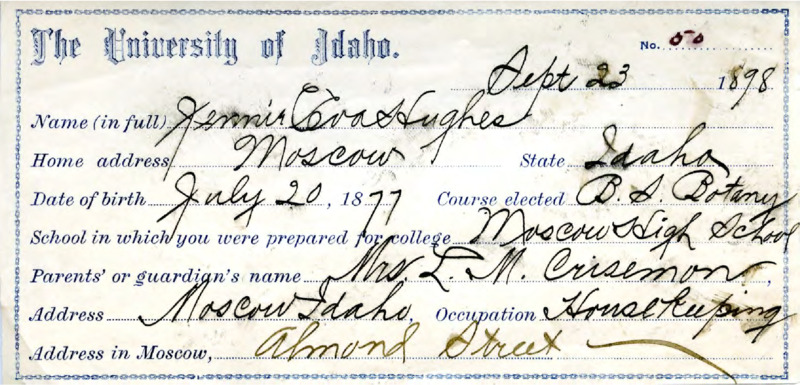

After a few years in Indian Territory, the Crisemon family moved to Idaho, where, according to the Census of 1890, there were only 201 Black Americans in the entire state. The Crisemons became the first Black family to settle in Moscow, Idaho and were famously well-regarded in the community. Lewis was a successful businessman, operating a local business that was most likely either a restaurant or a barbershop - two occupations traditionally open to Black Americans on the western frontier at that time. According to Jennie’s University of Idaho registration card dated September 23, 1898, her mother’s occupation was housekeeping.

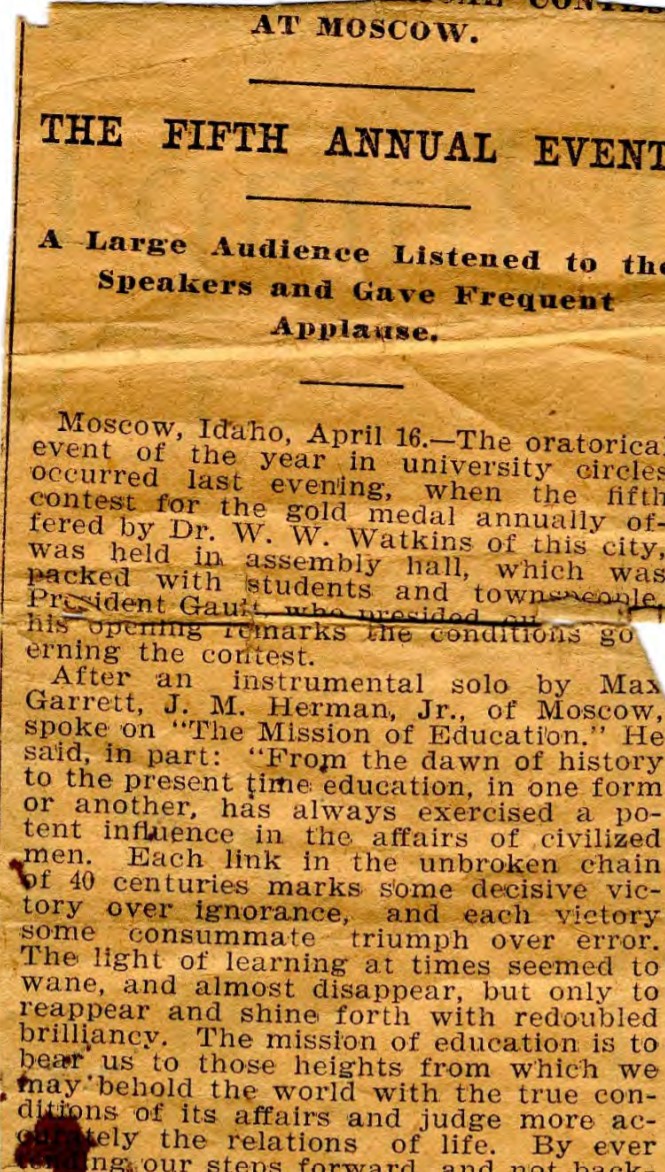

Although some western states restricted enrollment of Black students in public schools, Jennie was not prohibited from attending Moscow’s public schools. She graduated from Moscow High School on April 26, 1895. According to historian Keith Petersen’s book, “This Crested Hill: An Illustrated History of the University of Idaho”, Jennie “accumulated an admirable academic record.” She won the prestigious Watkins Medal for Oratory in 1898 and graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree as one of seven students in the Class of 1899.

The materials shown here include the speech that won her the prestigious award, along with a newspaper clipping from The Idaho Spokesman that explains that the judges decided to award the prize to Jennie since her performance “was received with vigorous and long continued applause.” “Miss Hughes is a member of the junior class, an excellent student, and the only colored student in the institution. Her oration was well written and her delivery excellent. The contest was the best thus far in the history of the university, and reflected high honor on all the participants.”

Jennie died at the age of 60 in Spokane, Washington on August 19, 1939. She had four children with husband George Augustus Smith. Three of their children graduated from high schools in the Spokane area and one, Berthol Augustus Smith, was the second Black student to enroll at the University of Idaho but unfortunately died unexpectedly in 1919. Another child, Leonard, earned a law degree, possibly from Gonzaga University, and practiced as an attorney. The final child to pursue higher education, Ralph, attended what was then called Washington State College (now Washington State University) in Pullman, Washington, and graduated in 1935 with a degree in Electrical Engineering.

In a speech to her classmates at the time of their graduation, Jennie urged them to “occupy positions of usefulness.” Because Jennie left neither letters nor a diary, it is not known if Jennie herself believed her life had been one of usefulness. But there is no dispute that history remembers Jennie as a remarkable woman who, at a time when less than one percent of Americans earned a Bachelor’s degree (and even fewer Black Americans), Jennie seized the opportunity of education and left an inspiring legacy of determination and distinction.

Sources

Photos courtesy of MG 5758, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives

This essay was first published in February 2020 by the University of Idaho Library’s Michelle Shannon on the Idaho Harvester Blog. Shannon was working with researchers from the Black History Research Lab when she produced this research