A Course for Black History

by Derek Higgins

1960s Context

The 1960s saw tremendous growth and success athletically for the Vandal programs. Two important athletes who contributed to this success were Gus Johnson in basketball and Ray McDonald in football. Johnson was only at Idaho for one year but averaged 19 points and 20.3 rebounds per game in route to helping the Vandals to a 20-6 overall record. After he earned All-American honors in 1963 Johnson was drafted in the second round of the NBA draft by the Baltimore Bullets. He went on to spend 11 years in the NBA, garnering five NBA All-Star selections, four All-NBA selections. He was inducted posthumously into the Vandals Hall of Fame in 2007 and the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2010. Ray McDonald played three years for the Idaho Vandals at running back. Due to his size (6-4, 240 pounds) and speed (9.9 second 100 yard dash) he earned the moniker “Thunder Ray”. Garnering two All-American honors, Ray rushed for 2, 916 yards and 39 touchdowns during his career (which stood for over 20 years as an Idaho record). Taken in the first round (13th overall) of the 1967 NFL Draft by the Washington Redskins, McDonald was the first Idaho Vandal ever drafted in the first round. He was inducted posthumously into the Idaho Vandals Hall of Fame in 2008. While Johnson and McDonald were two of the most notable Vandals of the 1960s, another student athlete was working in the late 1960s to bring about a better understanding of black culture and history for the mostly white campus.

Petitions for a Black History Course

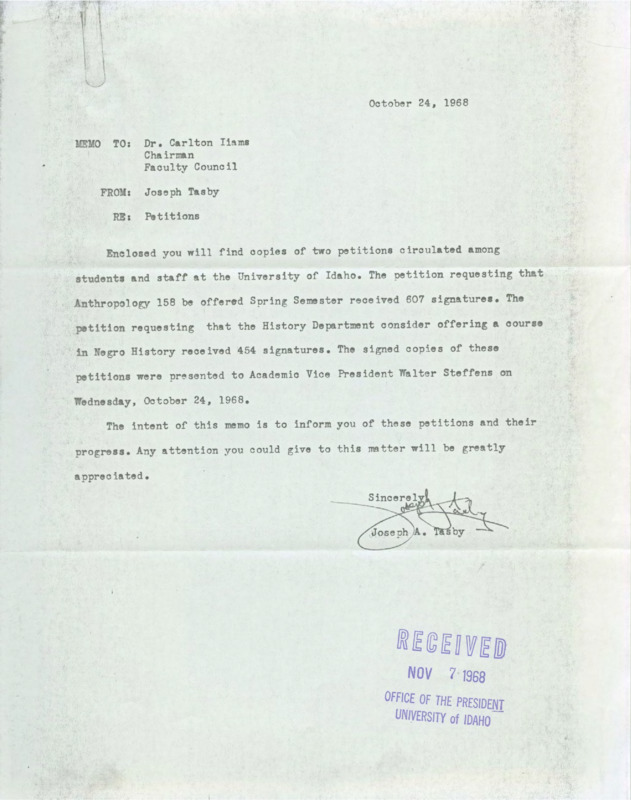

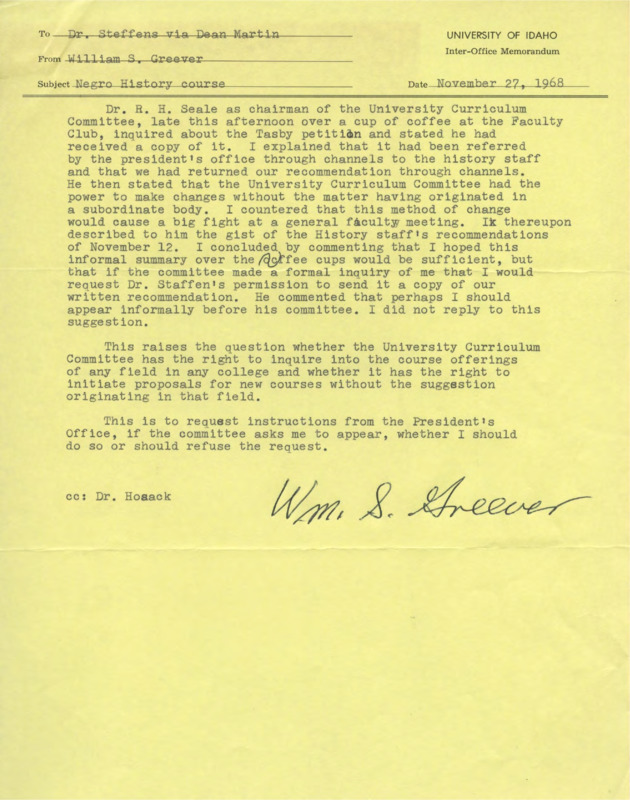

Joseph Tasby, a black student athlete on the Vandal football team, circulated a pair of petitions in the fall of 1968 asking the university to re-activate an Anthropology course dealing with race, and the creation of a course in Black (or Negro as it was termed at the time) History course that would also have a black instructor. Both petitions garnered many hundreds of signatures in support of these goals. President Ernest Hartung wrote a letter back to Tasby acknowledging the receipt of these two petitions and the importance of these two issues and asking for patience as the university looked into fulfilling these requests. He ended the letter by saying, “We appreciate your interest in pressing on these matters and feel that if the courses can be implemented in the manner and spirit you have suggested them, the University will undoubtably be a better educational institution as a result.”

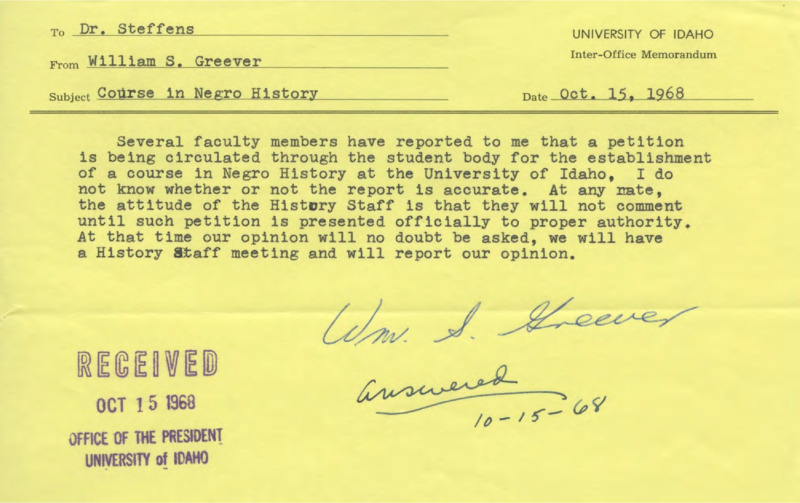

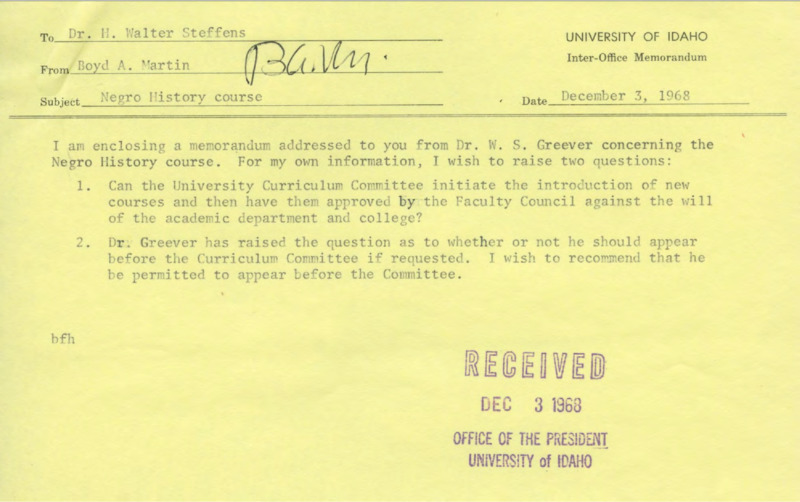

The History department responded to the request at a department meeting where they discussed whether they could accommodate the creation of a black history course and how to go about hiring a black instructor to teach it. Upon examination of the course load it was determined by the department that an individual course on black history was not necessary as all the aspects it would cover were already being taught in the various history courses being offered, so a standalone course would create redundancy. It was also pointed out that there were not individual courses for women or Jews or other ethnic or minority groups so taking this stance was not a new position for the department or the goals they had established in how to teach history. In response to finding a black instructor for the department, it was pointed out that there had been times in the past where they had tried to hire or contact black instructors before but they did not have an interest in coming to Idaho, nor had other similar universities had much luck in similar circumstances. This was not the final word though, as changes would be happening sooner rather than later.

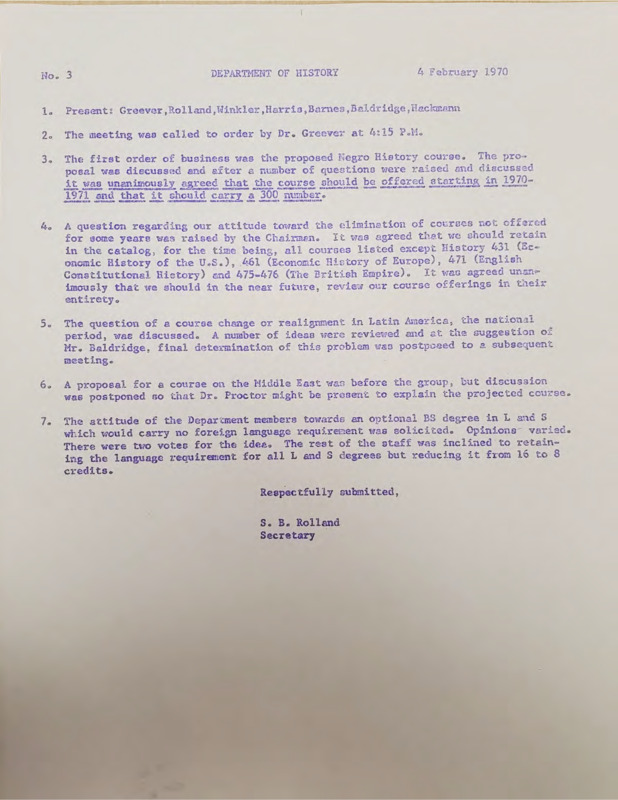

The historians filed into the cramped conference room at the Administration building for another History Department meeting. It was early February at the University of Idaho and, like every year since 1892, preparations for the upcoming school year were already well underway. As Dr. William Greever, department head, called the meeting to order at 4:15 pm, the group’s first order of business was both new and yet strangely familiar. A topic that had been discussed amongst these very historians around this very table a mere thirteen months earlier, the idea of a dedicated Negro History course at the University of Idaho was now a distinct possibility.

Success

January 1969 had witnessed multiple meetings amongst the historians as to what kind of response they would have regarding a petition circulated amongst the students that called for a Negro History course to be taught at the University of Idaho. Signed by over 400 students, it was but one piece of evidence that the national pulse on civil rights was creeping onto the Palouse. Much debate had ensued amongst the old guard, and after multiple hours of discussion, they had reached a decision. Elements of Black history were already present in the currently offered American history courses. Surely no individual course was needed, for other races and sexes got no special treatment. Dr. Greever insisted that they would love to provide such a course, but fairness to all topics involved meant that there was neither the time nor resources to pursue the matter any further. If the University of Idaho wanted a course in Negro history, it would have to wait a little longer.

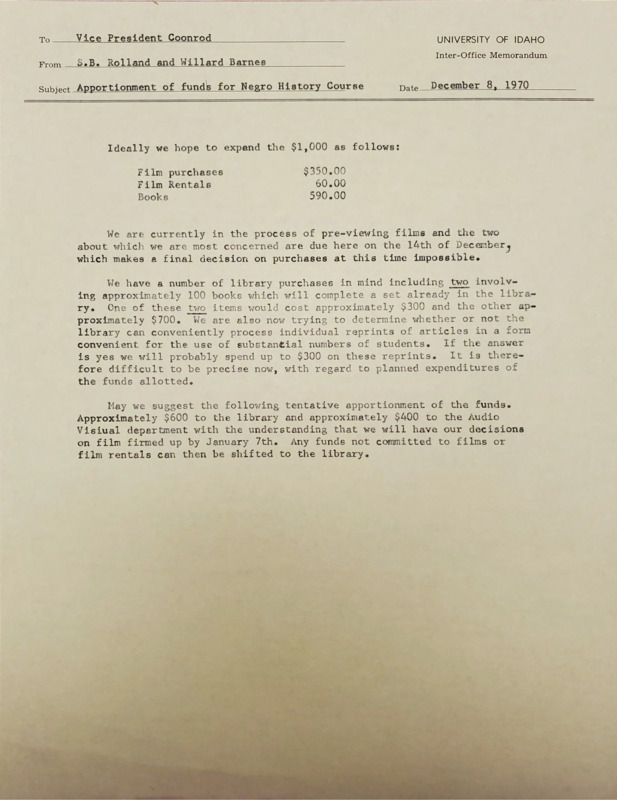

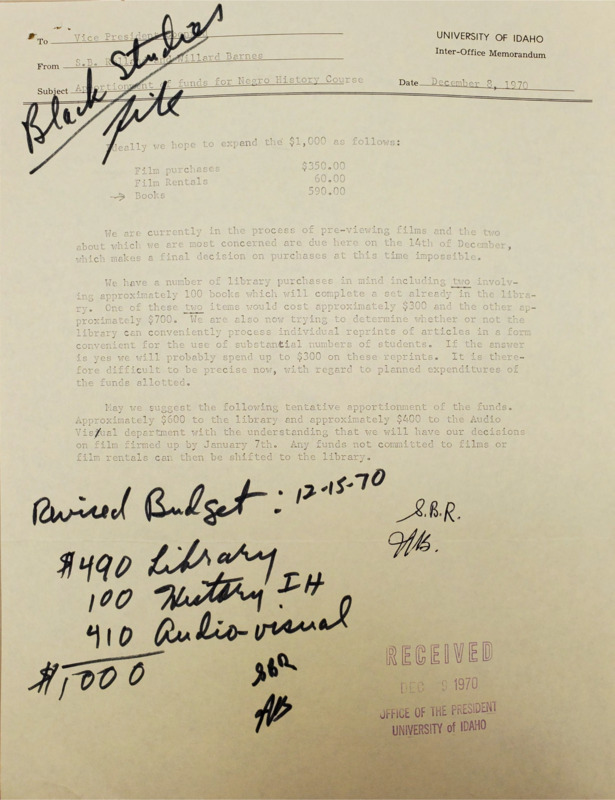

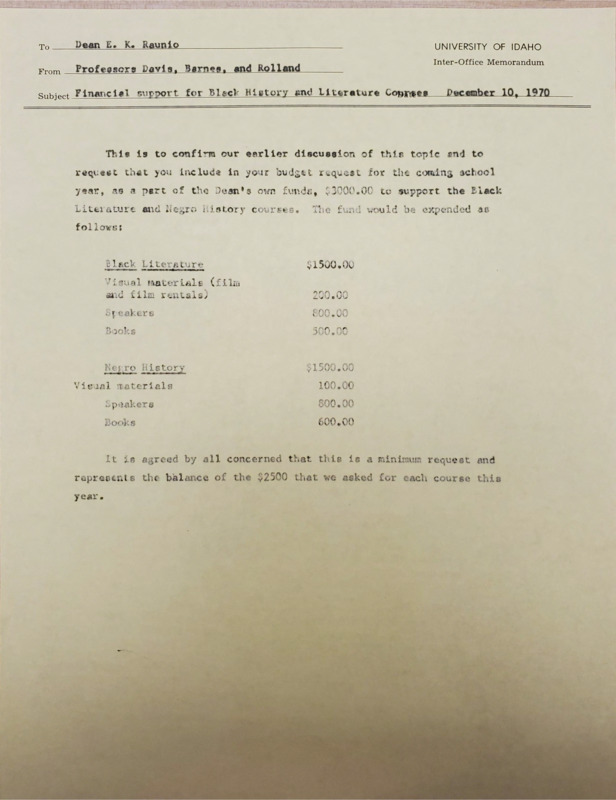

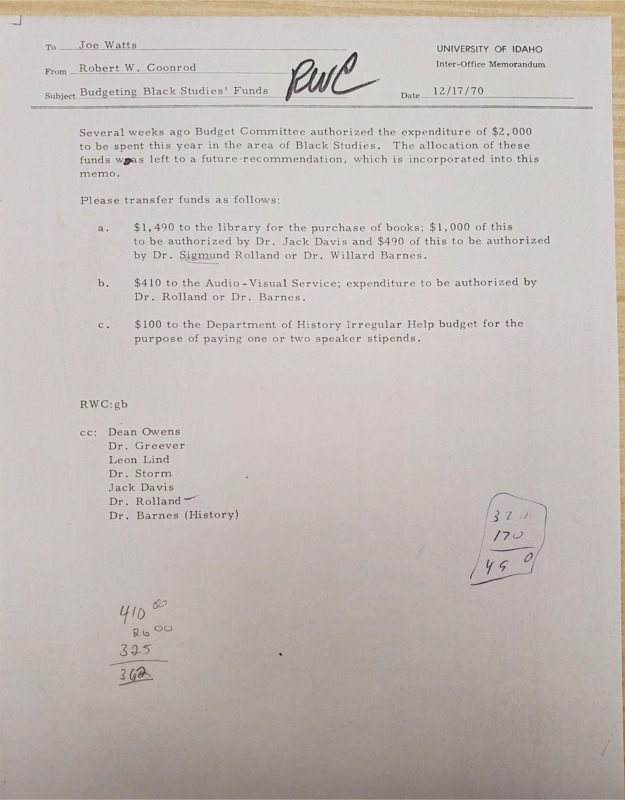

Playing the waiting game was not something the students would have to do for very long, as the topic these gentlemen historians had no time for in 1969 was back on the docket in 1970. Like blowing on the embers in a dying fire, the memo circulated by Doctors Willard Barnes and Siegfried Rolland breathed new life into the idea of a dedicated Negro History course. Highlighting substantial student interest and adequate teaching materials, they implored the important experience that such a course would provide for not only the Department but the University as well.

As the minutes ticked by, and more details and opinions were discussed amongst the professors, only the impending, all-important vote would signal whether 1970 would be any different than 1969. Eventually, a vote was taken, and passed by unanimous agreement that such a course would be implemented in the 1970-1971 school year. The change that Joe Tasby sought, that students on campus had been clamoring for, was now beginning to come to fruition.